We receive over 170 thousand Terawatts of energy from sunlight every second. In theory, that is enough to power 10,000 times the world’s total energy use. Despite this, we have an ongoing energy crisis from oil and gas supply-demand disruption. Well, we may receive lots of sunlight, but harnessing, converting, and storing them into usable forms are the tougher parts. Currently, we harness this power of the Sun through residential and commercial solar rooftops or utility-scale solar farms. Residential and commercial solar installations are considered small-scale solar projects (under 100KW). The added capacity of small-scales projects pales when compared to utility-scale, at ~10GW, accounting for merely 1/3 of the 33GW US Solar PV installations in 20231.

This is a classic case of volume vs profit. While utility-scale projects enjoy massive volumes with large scale operations, profit pools reside in residential segment as it benefits from favorable pricing.

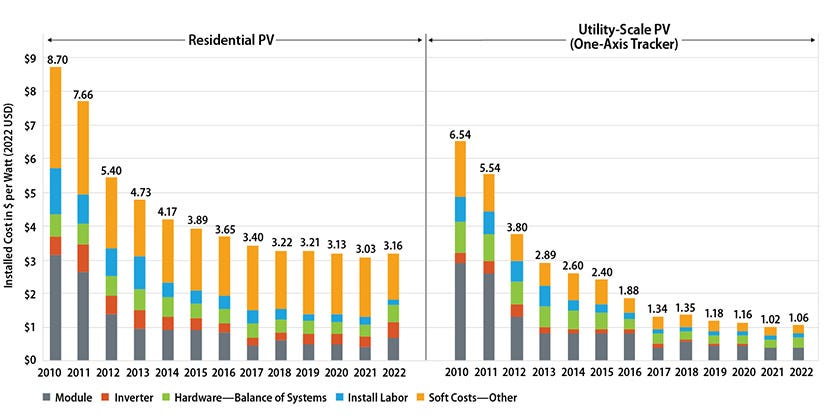

In either case, a host of other components come along when installing solar panels, one of which is solar inverters, devices that rapidly switch the DC input received from the solar panel on and off to create a simulated AC waveforms that conforms to household usage. Inverters are mission-critical components in a solar ecosystem but account for only about 5-8% of the solar installation cost.

Enphase and SolarEdge are currently the two largest inverter brands within US household residential and commercial space. Founded in 2006, Enphase commercialized microinverters with its initial “M” series until 2017 when it started to ship its “IQ” series products (currently IQ8). Backed by GE venture capital, SolarEdge was founded in 2006 and sells power optimizers, with the latest version being its S-Series. Both companies have strong technological and software roots with Enphase being managed by Indian-dominant management team while SolarEdge’s has a strong Israeli root.

Return profile across the solar PV ecosystem. Compiled using data from S&P Capital IQ.

Solar industry profit pools calculated using data from S&P Capital IQ2

Before we go further into these two inverter companies, let me invert the problem by rejecting all other solar components as investable ideas. The solar ecosystem (refer to no.3 at the end of the article) consists of polysilicon (raw material), solar module (solar panels), solar glass (protective layer), solar EVA films (prevent degrading), solar trackers (tilt panels towards sunlight), project developers (design systems, secure permits, and bundle components), energy storage system (batteries), and solar inverters (convert DC to AC). When I looked at profit pools distribution and returns on capital across the entire solar sector, I rejected the rest one by one.

Polysilicon is a commodity business with volatile return profile fluctuates around the polysilicon market price, and I am not skilled enough to get the cycle right and pick the low-cost players.

Solar modules (the solar panels themselves) may seem like an obvious choice for solar stock investment, but it is frequently plagued with industry over-supply from Chinese competitors monopolizing the upstream process. Module producers require both cost reduction from large manufacturing scales and pricing power that comes with technological break-through on solar efficiency, a seemingly contradictory relationship as each new technology iteration resets production scales (making old manufacturing plants obsolete), as well as relative market positioning.

Solar glass has decent margins, but its wide market applications (building, automotive, electronics) and large production scales means a heavy asset base. I have yet to find a “pure play” solar glass producer.

EVA films have great margins and returns in the past, but it lacks a sustainable moat since its production is simply just mixing readily available plastic materials, with poor competitive dynamics from Chinese players (Hangzhou First and Shanghai HIUV entering price wars).

Solar trackers also have a decent return profile, but I don’t like its customer base skewed towards utility-scale customers who have the upper hand in bargaining power. Project developers have low margins and poor returns.

Energy storage players operate at sub-scale to be profitable and have similar issues as the glass players with battery having wide applications that require large scales.

That leaves us to our little solar inverters, accounting for about 12% of revenue share but enjoys 21% of industry profit share, with an average EBIT/IC of 40-50%.

Driving factors for return on capital come down to the margin profile and invested capital of the underlying business. We understand why margins are high by looking at the relative bargaining power across the supply chain and competitive landscape within the market, as well as understanding the rationale behind the low capital base by looking at what the business owns and what it outsources.

Graphical depiction of how each of the three types works. Source

We have three types of solar inverters: string/central, microinverters and optimizers.

String/central inverters are the most preferred among large-scale solar farms since they are the cheapest on a per-watt basis. The idea is to string the current together in series and convert at one-shot with 1 inverter. Using elementary physics, we know that since the circuit works in a series, if one of the panels has lower power output, it lowers the current for the entire system. As such, the maximum output from such a setup is capped by the smallest panel.

Enphase designs microinverters (MLPE), mini-sized inverters installed right next to each panel in parallel circuit. This makes each panel inverter output independent of one another and addressed the issue mentioned. String/central inverters make sense for utility customers since such large-scale solar farms are usually set up in places like deserts with minimal shading or obstacles. Meanwhile microinverters, such as the one produced by Enphase, are a popular choice among rooftop household users because it prevents lower-output panels due to shading from trees or other buildings power-capping the entire system.

SolarEdge solves this issue by pairing string inverters with power optimizers, an option that sort of combines the ideas of both. SolarEdge users would have a similar string inverter that converts all the current, but also have individual power optimizer at each panel to regulate the voltage to ensure consistent current, to prevent any panel from dragging down the power output of the entire system. So, the key difference between the two firms is the customer mix and product types, with Enphase heavily skewers towards an almost 100% residential mix while SolarEdge has a 60/40 mix on commercial/residential share.

Solar industry usually comes with layers of middlemen including distributors, project developers, home installers, and financing partners. The way they influence decision-making depends on which customers they are selling to. In the case of residential solar, home installers influence is a friendly middleman that prefers some brands and recommends them to rooftop solar users. Installers teach homeowners about the nitty-gritty of a solar ecosystem, highlight differences of using each technology, and compare brands and price for them. As for the utility and commercial customers, the project developer is an unfriendly middleman to the component producer as they receive competitive bids from vendors and turn the sales process into price competition to get the lowest price per watt.

So, the moat of a residential solar inverter is essentially the name brand recognition from local distributors who stock up inventories, as well as the installers who recommend the brands to homeowners. Based on this aspect, Enphase’s nearly 100% residential mix seems to give it an edge in both ASP ($0.4/watt) and margins (35-40%), as compared to SolarEdge’s numbers ($0.2/watt and 30-35% GP), due to the drag from its 60% commercial mix.

Well, is that really all to the story? Knowing that solar projects tend to cost a lot for homeowners (typical project costs $30-50K), it is hard to simply rule out the pricing factor completely. As I dig deeper, it turns out that Enphase and SolarEdge give Special Pricing Agreement (SPA) and Special Incentive Programs (SIP) to distributors as ways to push for products and brands. Distributors would get a rebate if they do manage to hit a pre-determined growth target set up by Enphase and SolarEdge. A distributor would incentivize installers and end customers to go for certain brands, and receive, say, $60 per unit rebate from Enphase for each unit of IQ8 shipped (selling at ~$150/unit). In other words, since distributors themselves do not create demand, the two players are essentially buying volume share with lower pricing with these special agreements.

Installers typically sit on module inventory instead of inverters, they get supplies from local distributors as when needed. Obviously, installers influence homeowners in selecting brands, which factors in their technical expertise, local permitting requirement, ease of installations, as well as the warranty and support comes under each brand. Installers generally do prefer inverters that are somewhat durable to avoid subsequent trouble that comes with RMA (returning and replacing when something goes wrong).

It is only natural that, with each new installation, installers develop their technical expertise in not just matching the right type of inverters to the right setup, but also brand-specific product knowledge that prevent installers from deviating too far from the mainstream brands. This strengthens the incumbent players who then build on additional product features upon receiving feedback from installers. Enphase has accumulated over 900+ installers in its tier-based partner networks and SolarEdge has over 5000 residential installers. More is not always better, as quality control may become an issue.

Nonetheless, this installer network is fantastic in facilitating new sales during upcycle, but can be equally devastating during down cycle, where orders can be cancelled when getting a permit does not lead to installation (there’s usually a lead time of a few weeks, where anything could go wrong). Any subsequent misfit identified between the module and inverter may result in product or brand switching. Installers’ credit cycle is tight from design to equipment procurement to installation and inspections, and many do not want to risk holding on obsolete projects.

Sometimes, homeowners may choose to use a 3rd party owner, a commercial entity like Sunrun that pays upfront installation costs and leases the power back to homeowner under a power purchase agreement. Here, both Enphase and SolarEdge appear at the top of the Approved Vendor List (ASL), preventing smaller brands from taking shares from them. But I doubt they account for a large share of volume anyway.

Inverters are asset-light businesses as compared to module producers, as brands do not own production facilities but outsource the assembly process to contract manufacturers.

Enphase engages Flex, Salcomp and Sunwoda for microinverter assembly/testing, Sinbom for AC cables sourcing and ATL for battery making. Likewise, SolarEdge engages Flex and Jabil for its inverters and Kokam for battery production. Domestic sales is produced within North America, while productions in Eastern Europe, Mexico and Asia serve oversea customers for faster lead times and lower costs.

This outsource manufacturing is key to the high return on capital from Enphase and SolarEdge as it lowers the capital base and simultaneously allowing them to leverage up their scale when demand is flooding in. The capital needed for production instead flows to more valued-added services such as research and customer support centers, with Enphase’s R&D expenses over 2x its Capex while SolarEdge’s 1.8x.

In theory, this should enable GP margins to scale up with 2/3 in variable manufacturing costs and 1/3 fixed supporting cost (e.g., warranty & customer service), all while improving invested capital turn as they do not need to hold much inventory in production. But in reality, the negotiation process between Enphase/SolarEdge and its manufacturer is more nuanced. There is a choice between 1) paying extra upfront for minimal order volume, or 2) having flexible scales but compensating with under-utilization fees when things don’t go well.

In either case, what I am trying to say is beneath the surface, the brand owner’s power may not seem to be as strong as you think. I doubt Flex would consider Enphase and SolarEdge such important customers to be given all the favorable terms. The true test of whether you have bargaining power is to see if there is a way to truly flex (pun not intended) your costs up and down, making either your upstream or downstream absorbing the costs as they need you more than you need them.

For this, the EMS seems to be in a better position as compared to the brands, with adaptive models that adjust quickly to volume change (e.g. ODM Voltronic Power’s Q3 sales down 30% while maintaining GP margin). As recalled from SolarEdge Q3 earnings call, this is what management said about its cost level:

I would like now to address the decrease in our gross margins in the third quarter and provide color on the fourth quarter and the quarters ahead. Our cost of goods sold are comprised of variable costs that are correlated to the product mix and volume shift, such as manufacturing costs, shipping and logistics expenses, et cetera. In addition, we have other indirect costs that are not volume or mix specific, such as warranty costs related to our existing and growing installed base, contract manufactured claims related to adjustments made to the manufacturing levels and costs associated with our operation and support department, et cetera. These costs are not correlated to the volumes of product shipped and usually require some time to be adjusted to significant changes in revenues.

Management cited “Contract manufactured claims related to adjustments made to the manufacturing levels,” reported a 20% on GP margins and guided a meager 5-8% for its Q4, down from its usual 30% level previously. It struck me as a surprise when I read it because I thought SolarEdge would be at a position where they are at the upper hand in cost absorption.

Similar dynamics exist downstream where SolarEdge is forced to take back some of the inventory from distributors, ballooning its working capital from 124% of sales in Q1 to 200% of sales in Q3.

Unlike Texas Instruments where it is selling chips with outdated tech, SolarEdge is holding onto leading edge devices, and risking high inventory obsolescence cost that could further hurt its margins when they are displaced by next generation of tech.

This double whammy of declining margins and IC turns has collapsed SolarEdge’s apparently high ROIC. This call was the trigger in late October for the collapse of the stock prices of Enphase and SolarEdge.

While some investors may trade cyclical factors and look to sellout and buyback when cycle bottoms, I am more concerned on the fact that SolarEdge is getting squeezed on both ends of the supply chain (distributors are also sending back excess inventories), and I don’t have as much confidence to claim that it has strong bargaining power.

Enphase on the other hand, does not have seem to suffer on same degree in Q3, as its margins have been intact at around 48% while it is guiding 40% not 5%, with okay inventory level. Although I do think Enphase does have better positioning in negotiating with its suppliers and distributors, it is far from being immune to downcycle at all.

But as we learn more about NEM 3.0 later (Enphase cited 25% decline in sell-through Q/Q), this is simply a time-bomb because outstanding orders built out in Q1-Q3 have yet to be fully absorbed, but that is likely to come to a sharp turn going into Q4 or Q1 2024 with the downcycle starting. The inverter issue is not about having a downcycle, but how the two firms reacted during such downcycles that alarmed me.

Sales and margins compared, data from official sources.

Now that we have learned a bit more about the dynamics across the supply chain, what about the competitive landscape between them?

Enphase has a unique microinverter product with no close domestic substitute, a strong brand where consumer recognizes its lower failure rates, and a network of installers that serves as advocate to push for its products, thus its relative positioning fetches itself a factor of 1.5x in ASP when compared to SolarEdge.

Enphase maintains this brand image by continuously investing its installer network, and even when something goes wrong, offers customer service with average call wait time at merely 1.3 minutes (to maintain low-cost structure, they are done remotely with mostly Indian workers). Enphase’s next stage is to build a host of different software and hardware for all-in-one home energy solutions. In trying to become “the Microsoft of household energy.” Enphase ventured into storage in 2014 and EV charger later, and now it is rapidly extending its services into software capabilities.

SolarEdge, on the other hand, has a more balanced mix of two end markets, and seems to sell a cheaper alternative that aims to provide better value for dollar. Despite being the number 2 in brand recognition among households, SolarEdge has a strong hold on the commercial customers, as it often partners up with distributors and customers to help design solar systems. This consultant approach is what seems to be helping them to win over many commercial projects over time. Enphase’s volume growth is a bit muted as compared to SolarEdge’s growth. This makes sense, given average volume for commercial projects tends to be larger compared to average household projects. One of the largest projects that SolarEdge has ever done is the 77 MW floating solar farm in Taiwan. This dwarfs in comparison to Enphase’s 4.5 MW project in Karnataka.

The model for Enphase seems superior in that you get ~1.5x in ASP over SolarEdge with volume at half, so it comes down to a GP margins gap of 5-12%. While there is a GP margin difference of a few points between residential and commercial customers, this is offset by the lower warranty cost on SGA basis (hence the SG&A margin gap of 5% between the two). So, all-in-all, Enphase still wins on its ~20% EBIT margins that 2x SolarEdge’s 10%.

Looking back on Enphase, the strategy is surprisingly simple. Every time there is a new generation of IQ series release, efficiency increases with price per watt declined but volume sold exploded, driving up total sales growth. Enphase launched its IQ7 in 2017 where volume more than 2x to ~2GW where ASP fell 16%, although NEM 2.0 is probably the larger driver in this case. In 2021, Enphase launched the IQ8 series capable of providing a backup power without battery, driving up volume 60% for 2 years in a row. But even on a per unit basis, this time round Enphase seems to have a hold on its pricing power, gradually raising its price from around $100 to nearly $150 per unit with the inclusion of battery sales now.

Absent the commercial customer profile means there is no intense price competition unlike SolarEdge where competitive auction is used for selecting vendors. Based on what the company has hinted so far, the next generation (IQ9) is likely to come online by 2024. So, the product cycle for Enphase is approximately 3-4 years. With each iteration of products, comes a host of value-added capabilities such as software upgrades, grid supply optimization and smart monitoring systems, something that really appeals to residential users. There is something cool about having all the energy control interface at the palm of your hand, though I doubt this is something that SolarEdge or any competitors cannot replicate.

I think it all comes down to its no-failure brand image and the level of customer service, which upkeeps its NPS at 50 vs 18 for SolarEdge. Bear in mind that this is a metric that the company keeps a close eye on for each earnings call (claiming that it reaches 70+). It crafts its installers reward program into platinum/gold/silver based on homeowner NPS responses, with Platinum tier requiring NPS of 50.

SolarEdge Customer Mix and Margins, from management earning calls.

SolarEdge on the other hand, built its strong positioning among the commercial customers, and often serves as a consultant/helper role in helping customers specify/design solar systems. Usually, such a consultant approach, such as the one seen in Spirax-Sarco would add enormous value to customers if it were complex projects. But solar ecosystems are not as complex as steam systems by Spirax-Sarco that have huge energy cost saving when done right.

As you see from the chart above, incremental share of commercial mix leads to lower ASP and margins, a relationship that is repeatedly emphasized in this post. On the residential end, SolarEdge would make similar claims on building this all-in-one systems ecosystem claims the same way Enphase does, and I honestly do not think they are any less in delivering those software capabilities. So, from the eye of the residential users, it really comes down to the specific needs of each homeowner, with Enphase lower failure rate well-recognized but those who do not care choosing SolarEdge for its lower price. So, it seems like the market dynamics are relatively stable among these two, with both getting a larger share of the pie, establishing a duopoly situation at the expense of other fringe players4.

Sales breakdown by volume and price, data from official sources.

See the table above. Both Enphase and SolarEdge had decent growth rates north of 30% per year on average, driven almost entirely by volume. This is no surprise given factors in residential solar adoption, new product releases and favorable user benefits from net metering.

Just like many other new tech, the diffusion process of a high-end product is typically marked by a gradual decline in ASP while experiencing explosive volume growth. For example, cell phones were sold at nearly $4K in the 80s with <1% of the population owning one5. Today, over 97% of American population owns a cell phone, with average price dropping to a few hundred dollars. If we look at cell phone prices with the type of function it provides, this decline in pricing is even more drastic.

Similarly, as product efficiency increased and unit production cost improved, the massive 42% growth in installation capacity for Enphase is accompanied by a 3% decline in pricing (take note that this is a simple average. If we take that ASP collapsed from 67 cents to 39 cents in 10 years, the annual decline would be 5%).

The weakness of this model is that, since solar panels and inverters alike are equipment that has long life cycle, these are essentially one-time sales that are not recurring. At some point the growth would reach some level of maturity where growth would slow to its natural replacement rate (albeit inverters seem to have shorter lifespan than panels). So, the key question in growth is understanding how far we are away from market saturation.

This situation is unlike in many other heavy equipment businesses, such as elevators and wind turbines, company build out large installed base but come with a highly profitable aftermarket sales in either maintenance or software. In solar inverters, there is no such aftermarket sales since maintenance is included in the upfront price as warranty, and frankly if one of the microinverters/optimizer is not working, user simply throws it away and replaces it with a new one instead of fixing it.

What about pricing?

For the cheaper Chinese branded string inverters without any optimizer, they could cost less than $1K only.

SolarEdge would cost somewhere in between the Chinese imports. If we assume power output at 300W with 6kW panels installed per household, this translates to about 20 panel. That that translates to $1.1K for the SolarEdge String Inverters and $50 on each optimizers (assuming 1:1 pair up), which is about $2K in total.

For the more expensive microinverter from Enphase, each device costs $150, or $3K in total.

Hence, the cost differences between Enphase and SolarEdge goes up linearly at $100 for each panel, so making larger-scale commercial projects a tough sell for Enphase (SolarEdge also pairs 2 or 4 panels to 1 optimizer to reduce total costs for its commercial offer).

The price gap of 3:1 from Enphase compared to the cheapest brands may seem exorbitant to a household owner, but when compared to the total installation cost of a solar system that is estimated to cost around 30K to 50K, a 2K increase is only a 4-6%. In exchange, not only do you get faster payback period with all the software features that optimize when to return the power back to the grid, but you also get great customer support and after-service, as inverters are frequently the point of failure for a solar ecosystem.

Solar inverter (Red Bar) accounts for a small fraction of overall costs, source

As with many renewable sectors, regulation/policy can be a strong driving force for technological adoption.

Net Electricity Metering (NEM) is the idea where homeowners can sell unused electricity back to the grid, and it has been one of the main reasons driving up solar installation in the US. This is particularly important for markets such as California where the electricity bill is higher than the national average and major utility firms have been given green lights from regulations to hike up rates.

To illustrate the impact, I could use the example of the phasing out of NEM 2.0 in California into NEM 3.0.

NEM 2.0 was introduced in 2017 to encourage homeowners to install solar panels by giving them favorable terms when unused power generated from the panels is sold back to the utility firms. This means the excess electricity in California was sold at generous rates (~0.3/kwh), not only offsetting a normal bill but even making money out of it.

This combines with two other positive aspects: 1) solar systems are usually designed to produce more than what people use, and 2) annual billing structures where credits can be accrued on months with high electricity generation to offset months with lack of electricity.

As such, solar panels typically work out to have around 4-5 years of payback period. Such favorable terms have made it an easy sell for the installers to justify high-end branded solar components, with inverters being the local brands Enphase and SolarEdge.

However, this creates a significant amount of burden on the utility side, as 1) homeowners not paying for power transmission cost those accounts for a large part (power and transmission assets account for >75% of gross assets in PG&E) of their maintenance capex, 2) solar power has severe baseload issue when the sun does not shine on the nighttime and the grid is overhauled with power consumptions, forcing utility companies to invest in storage to maintain its baseload.

As such, NEM 3.0 was introduced to reduce rates received by homeowners when they sell back electricity (~0.05/kwh), but also introduce monthly true-up terms that have variable rate structure depending on whether the grid needs the power.

An exemption period was created between December 2022 and April 2023 for homeowners who obtained permits to be grandfathered under the old NEM 2.0, thus leading to a frenzy rush into the getting solar orders. Some installers reported more orders in 1 quarter than the entire year, and that inevitably would lead to inventory cool-off and subsequent underperformance.

The impact of introducing NEM 3.0 would drive up battery attachment rate as the rationale for installing solar is more for offsetting existing bill rather than to sell it back at meager rates. The battery installed could be used to offset consumption at night with no solar power or when to be sold back only when homeowners see a better rate (hence you need that smart system from the inverters to tell you the best time to sell your electricity back).

With the shakeup of NEM 3.0 in California and its implications on the rest of the solar markets, we have the entrance of Tesla into inverter space in 2023.

Previously, Tesla has so far been strong in its Powerwall storage for its EV charger. Tesla entered the inverter market as a low-cost disruptor, introducing its string inverters with no-frill design at less than $0.15/watt, almost 1/3 the price as compared to Enphase’s. Tesla distribution is a clear weakness when compared to these two players, as it shuns the idea of using third party distributors and installers in favor of its direct selling approach.

But Tesla’s brand recognition and its software integration with its EV charger and Tesla is a very strong point against Enphase’s smart ecosystem selling point. Now, with NEM 3.0 introduced, battery becoming a must, suddenly Tesla gains an upper hand with its 60% market share in the battery space despite being the new player in the inverter space. While Enphase and SolarEdge are moving into selling more battery and EV chargers, Tesla is moving into selling more inverters, meeting each other in the middle, and each proclaims to become the one-stop solutions that homeowners need.

The second regulation factor that is a big deal right now is the Inflation Reduction Act. Qualifying homeowners can now claim 30% of the solar installation cost to offset their federal income taxes. More importantly, IRA helps solar inverters to receive production tax credit of $0.11/watt if they are qualified for US content requirements, which demands not only assembly to be done in the US, but also subcomponent sourcing.

This would benefit Enphase over SolarEdge as the domestic production mix is higher, and management has repeatedly cited IRA as the next growth driver (Enphase expects to ship 1 mil inverters from US manufacturing facilities from Q4 onwards and guided IRA benefits of $27/unit to lift GP margins by 8%).

I think the outcome of IRA depends on how it impacts volume, margin, and pricing. Assuming they do transition to local production, the ideal situation is a reduction in solar installation costs that drives massive volume gain, which leads to overall growth staying at 20-30% range for the next few years until it phases out in 2032. Of course, the use of outsourced manufacturing means everyone should be able to get access to local manufacturing, and either bid up production cost or drive down ASP when qualified for this subsidizes.

Margin is a tricky one, even if Enphase or SolarEdge is qualified for the credit, that may bring up their margins, but pricing drag may mean the same dollar amount in gross profits even when margin improves. For example, if the $0.11 benefits translate to $0.055 in pricing and cost reductions simultaneously, what we have is the same incremental gross profits per watt as the price reduction offsets the cost reductions (but GP margins improve since the dollar amount is down), leaving no change in ROIC.

So, the key question comes down to how the credit is split between consumers, contract manufacturers and brand owners. Answering this question brings us back to our first debate on the dynamics across the supply chain and competitive landscape. In other words, the contractor manufacturers, such as Salcomp and Flex, as well as end consumers, would naturally want a claim for these credits.

I think the key question in understanding growth in this sector comes down to assessing its TAM and understanding whether it has reached a peak adoption rate. As much as regulation and policy are pushing for it, I think we should think about the long-term viability of solar energy as the numbers are showing us a huge growth potential.

Electrification is obviously real with rapid adoption of EV around the world and all the talks around the idea of a bidirectional smart-grid. Electricity final consumption is projected by BNEF to peak at 51 PJs in 2032 from 38 PJs in 2023, which solar energy consumption on energy generation goes up from 5% to 25% under Net Zero Scenario.

If we zoom into the US residential markets, solar installations penetration is at 3-4% of household. Rosy projection may paint a fancy image of a 10-20% long-term adoption rate in the residential space, but if we really think about it, it is probably more realistic to get those power from the utility-scale solar farm when we consider factors such as grid integration and intermittency issues that is much better coordinated on the utility side. Installing a solar system in the US is troublesome not because of the hardware sourcing, but the soft costs involved with an inefficient permitting process that takes up a few weeks in lead time to get a permit in some regions. Total solar installations in the US are projected to reach 40GW in 2027, but the bulk of the increase (>70%) comes from utility-scale solar farms that both companies have no presence in.

With the domestic market getting more and more crowded, the international market is even tougher for Enphase and SolarEdge.

First, we can rule out Asia because Enphase has no presence there while SolarEdge takes a minor share. Both companies have no edge whatsoever when facing against many Chinese competitors who control channels with favorable cost structure and pricing.

The European market may seem to have a similar attractive residential market (~1 million household have solar installed out of 200mil EU households), facing an energy crisis from the Russian war that has been driving up adoption rate. But the competitive dynamics favors the Chinese players over the US ones because consumers are more price-sensitive and acceptance on central and string inverters over microinverters and optimizers. In fact, Europe market has built up and over-supply situation that led to inventory issues in recent quarters, with the flood gate of Chinese suppliers coming in, and without the gatekeeper of channel barrier unlike the US (EU distributors are less fond of the high-end solar inverter brands in favor of low-cost Chinese brands appealing to price-sensitive customers).

This gives us a glimpse into one possible future scenario as to if the Chinese players do manage to break-into the US residential space and take up a large share, by then the investment case for these two inverters is basically over. The Chinese solar inverters (Sungrow, Ginlong and Goodwe) are equally attractive on a return on capital basis, but unlike the US ones they are much more exposed towards utility-scale and commercial customers, which means they succumb to the same fate as their module producer’s counterpart of competitive price bidding, rendering countless battle of price wars (Sungrow sells at ~$0.04/watt as compared to SolarEdge’s $0.26/watt).

As much as their growth has been impressive (Sungrow managed to grow installed capacity from 10GW in 2016 to 77GW in 2022), the profit share per volume is much lower with string inverters being the main products sold.

In other words, the investment case made for them hinges on sustaining a large volume growth while gradually taking shares on the residential side for pricing enhancement, that is too hard a call for me to make.

On the other side, the two microinverter players in China are Yuneng and Hoymiles, with each sold around 1 million unit and $150-200 mil in sales for FY2022, translating to a unit price of $160-170, and a 40-50% gross margin that is comparable to Enphase’s $150 ASP.

But the price-sensitive Chinese consumers give no fuss about inverter technology and opt for string inverters, which explains why 80% of Hoymiles sales (98% for Yuneng!) coming from outside of China, primarily in the Europe. Hoymiles is entering into the US market recently, challenging the positions of SolarEdge and Enphase. Well, I don’t quite seem it as strong a brand as Tesla, having an established installer network, nor does it offer pricing that is ridiculously cheap, so I think it is at best going to take some fringe market share and benefit from favorable IRA credits.

Now, putting all the factors together, what kind of scenarios should we paint to assess current valuations of the two stocks?

I think the friendly middleman effect does warrant the two stocks with some sort of moat around it. But the durability of this moat is somewhat questionable to me after learning about the negotiation process and tactics such as special pricing agreements and under-utilization fees. The relative bargaining power of inverter brand owner is not as strong as other branded household electronics or industrial component producers.

Ideally, I would prefer to own, at the right price, solar inverter ODM player Voltronic Power, which has about 1/3 of its business in inverters and 2/3 in UPS and does not worry too much about competition the same way as the brand owners do.

I mean, these two stocks are not cheap by any standard, with SolarEdge traded at 22x trailing EPS and Enphase at 30x, even after 50% crash from its peak from 2021. The market is still placing a premium on the huge growth it had in the past to continue.

For SolarEdge, I don’t think I am even confident enough to value the company given its weak market positioning, I simply just give up on the case.

For Enphase, if we slap a 25% volume growth with 10% price decline, assuming IRA has no overall impact on dollar amount earned as the benefit is split evenly between price/cost cut, assume margins continue to scale to about 25-30%. With FCF conversion of 100%, this translates to about 400-700m annually, let’s just say they are worth around 25x CF at fair, that would give us an IRR of 6%. It does not strike me as attractive enough to own its share with this current valuation.

Notes:

*For the profit pool calculations, margins of 10% is assumed for polysilicon despite its recent 30-40% industry number, this is because I don’t think that margin level is sustainable in the long-run (industry margin was ranged from -3% to 13% from 2014 to 2020 before polysilicon price shot up)