HVAC refers to Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning.

Don’t blame me for using such a whacky acronym, I am just the messenger here.

HVAC devices uses refrigerant to transfer heat in and out of a place. The compressor (or expansion valve) adds (or releases) pressure to make refrigerant hotter (or colder) in a cycle. The refrigerant passes through two sets of heat exchangers (i.e. the coiled parts) where one fan dumps the heat outside through a condenser, while another fan blows through evaporator to generate cold air inside the house.

Refrigeration cycle illustrated, from here.

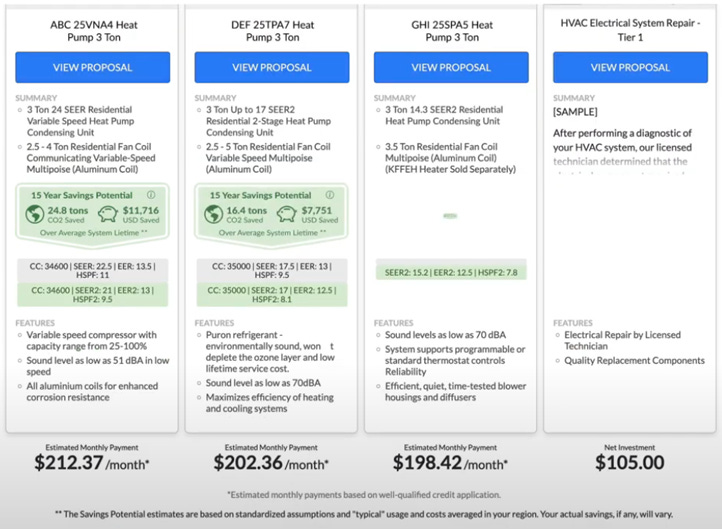

The ~$50B North American HVAC market is an oligopoly with high distribution barriers for new entrants. The top 8 players controls >90% of the market share. The competitive environment for OEMs is consist of the following players (brands):

1. Daikin (Goodman, Amana), with sales of ~$10B

2. Carrier Global (Bryant, Heil, Day & Night), with sales of ~$9B

3. Trane (American Standard, Ameristar), with sales of ~$14B

4. Johnson Controls (York, Coleman, Luxaire), with sales of ~$7B

5. Lennox (Armstrong, Ducane, Concord), with sales of ~$4B

6. Rheem (Ruud, Weather King), private company with similar size as Lennox

7. AAON (BASX), with sales of ~$1B

Market share analysis, from BofA Carrier Initiation Report. Left is residential, right is commercial.

This industry can be broken down into 3 major parts: 1) residential, 2) heavy commercial, and 3) light commercial.

For residential market, the critical success factors of residential HVAC come down to distribution network and technicians’ loyalty. This market includes heat pumps, furnace, and air conditioning (but not refrigeration) sold to homeowners, apartments, and condominiums. Residential HVAC products are not well differentiated. OEMs mass produce them in scales using standardized design, while sourcing components from the same group of vendors. So, the key idea comes down to distribution instead. In America, over 80% of families live in detached houses, making them very dispersed in geographic reach. I will go through more about this segment when I compare Carrier’s residential business with Lennox, as well as with Watsco as a distributor.

For heavy commercial market, OEMs’ selling points are 1) energy efficiency and 2) connectivity and remote monitoring to lower disruption cost. These are HVAC equipment for hospitals, data centers, warehouses, factories, etc. For such products, customization is the way to go. End customers have very specific and precise air/temperature control requirements since it directly affects their output quality. They do not like failure and high energy costs. The sales process here is relationship driven, and more direct between OEMs and end customers. I will go in depth for this segment when I compare Trane, Johnson Control, and Carrier’s commercial business.

For most parts, the light commercial market has basically the same market dynamics as residential. But sometimes it can be a sort of hybrid situation of the previous 2 mentioned. Some customers want lower costs; some want customization. These are the rooftop HVAC units at your retail outlets, office buildings and restaurant chains. They are essential for customer comfort and employee productivity. I will talk more about it when I go through AAON’s business model.

Let’s begin with Carrier Global as our first company.

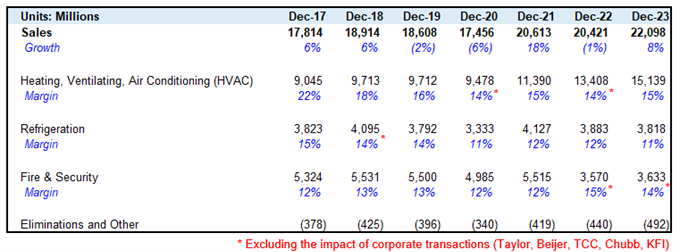

In 1908, Carrier was created as a subsidiary of Buffalo Forge using the modern air conditioning inventor Willis Carrier. In 1979, Carrier was acquired by United Technologies to diversify its revenue streams, until it was spun out in 2018 and now operates and trades as an independent company. It has grown to become the largest HVAC company in the US in terms of sales. The company has three business segments: HVAC (68% of sales), Refrigerant (17%) and Fire Safety (16%).

Carrier Sales and Margins, data from official filings, with exceptional gains/loss removed in margins.

The HVAC segment is a priority for Carrier. Its management has been quite clear about its intention to further strengthen its positioning. The segment sells air conditioning, furnace, and heat pump products to residential and commercial customers in ~40/60 split. About 3/4 of HVAC sales are for replacement units while 1/4 is from new construction units. The HVAC segment benefited from a huge sales runway during Covid-19. Sales went up from $9.4B in 2020 to $15B in 2023. Profitability-wise, HVAC had always led the pack with a stable range of 14-18%. Management acquired major stakes in Toshiba Carrier Corp to expand the channel reach and technology (e.g. variable refrigerant flow). Carrier paid $14B to buy German HVAC firm Viessmann to expand product range (e.g. electric heat pumps, smart home solutions), and to improve its weak European residential presence.

The refrigeration segment is more cyclical than HVAC. It hasn’t grown much in the last 5 years since the commercial capex cycle peaked, with margins declined from 14% to 11% due to lower volume. This segment sells products to keep things cold for commercial customers. Transportation takes up 70% of the segment sales. Think of keeping low temperature for supermarket chains to keep food fresh during transportation and laboratories for preserving bio-pharma samples. Carrier has been flushing out the less competitive units by divesting the food service equipment Taylor in 2018 and selling the Commercial Refrigeration business to Haier in 2024. For this post, unless otherwise stated, I would just lump refrigeration segment along with commercial HVAC, since it uses the same core mechanism mentioned at the start (HVAC is also known as HVAC/R, where R is refrigeration).

The Fire & Security business sells undifferentiated home security products, and Carrier has no edge in this business. These are smoke detectors, fire suppression systems, and alarm systems sold to residential, commercial, and industrial customers. The Kiddie brand products are sold in Home Depot and First Alert in Lowe’s. Price competition is rampant on the residential side due to strong retailer promotional sales and weak DTC presence. Segment margins have been okay, organic sales growth was 5-7%, but net sales declined in the last 3 years. Carrier has been slowly divesting businesses in this segment. It sold Chubb and KFI business in 2022-2023. It expects to complete the sales of the Fire & Security Access solutions to Honeywell in 2024 for $5B. For this post, I will not place any more emphasis on the Fire & Security market beyond this point.

Despite Carrier’s management is quite new, the direction of the firm hasn’t changed since the spin-off - A better focus on the HVAC segments and oversea expansion. David Gitlin is the current CEO of Carrier since 2019 and Patrick Goris joined as CFO in 2020. David served as Carrier’s divisional CEO prior to the split, and before that he was a president of the Aerospace Systems. Despite all these corporate actions, I don’t see any sign of strategic inconsistency. David knows where Carrier is going, and he has a plan to get there.

I will now talk more about the sales and distribution process that is crucial to this whole industry. No matter which segment are we referring to, it all comes down to the role of the middlemen. Residential HVAC value chain is very stretched out and has multiple parts. OEMs first load their inventory to local or regional distributors like Watsco, the distributors then sell to local technicians who arranged with homeowners to install the product. While OEMs market share is stable within the same top 7 companies, there are over hundreds of distributors throughout the national where it is highly fragmented, and there are >120Ks of technicians, and millions of homeowners scattered across America. For residential, the real customers are not homeowners but the technicians.

Distribution process of HVAC in simplest form, self-made chart.

The customer relationship is strong between homeowners and technicians, but not for the brands themselves. My point is that homeowners’ decisions are largely based on technicians. So, winning over these technicians is the key to win the residential HVAC war. However, OEMs don’t really hold any more real power over these local technicians.

The distributors are the ones who hold true power over these technicians instead. Many technicians are small moms-and-pops shops. They value robust training programs on how to install and repair new HVAC models, rebates, customer support and parts availability & lead time. Distributors hold power on both sides; they build inventory buffers to accommodate technicians’ request (technicians operate JIT). They also provide crucial feedback to OEMs to produce the inventory forecast months before the renovation seasons start. The distribution market is very localized where each market would have its own local champions. While LA, Hutson, and New York have strong Carrier presence, the west coast has not been so. More on the distributor side once we come back to talk about Wastco later.

While new construction is high volume and low margin; Repair and replacement unit has larger dollar sales with better margins. New construction is all about getting huge volume from major homebuilders like DR Horton and Poulte Group. Although they have good sales visibility, they buy in bulk, where margins for HVAC OEM are low. As for replacement sales, the time-sensitive nature of disruptive/broken air conditioning unit means existing homeowners do not have the luxury of comparing pricing. Arranging technician takes time. Homeowners often outsource the entire troubleshooting and installation to technicians as this segment has almost no DIY activity due to HVAC’s technical complexity. If a technician recommends a brand, chances are homeowner would go with the recommendation.

Think of it this way: HVAC is also a razor and blade business. But unlike elevators and aircraft engines, its shorter lifespan means a faster replacement cycle. So, the key to the residential business is more so from replacement sales, as servicing is not done by OEMs. It matters more for the commercial segment, which we will get there later.

Watsco estimated that only 15% of industry units are tied to residential new constructions. Long-term industry drivers for replacement sales are 1) OEM's push to shift demand from repairing to replacement, 2) regulation needs for energy efficiency (e.g. minimum SEER) and sustainability needs (meeting min GWP index). Short-term drivers have been 1) Covid-19 inventory pull-forward, 2) interest rates and household financing conditions. Again, despite all the noises around supply chain issues and price hikes during covid, short-term swing won’t be much of a discussion in this post.

Carrier tried to establish more direct channels in the past, but eventually gave up direct selling on the residential front to focus more on the core manufacturing activities. Ultimately, building out such a stretched-out distribution network to reach dispersedly located technicians and homeowners makes no economic sense for just selling one brand. Instead, Carrer started to partner up with large distributors like Watsco in each region, setting up multiple JVs and offering exclusive distribution agreements to entice Watsco to push for its products. But the results have been mixed. There have been past instances of bloated field inventory before, mostly noticeably in recent quarters. Carrier has weak channel coordination on the technician front. As a result, Daikin has overtaken Carrier's #1 spot in North America residential HVAC volume by aggressively gaining share on the technicians.

To put into context, Daikin is the largest HVAC company globally. Despite being a Japanese firm, its US sales mix has increased from ~10% in 2013 to 30% now, ever since the acquisition of Goodman. Whatever game Carrier is playing, be it cost, technology or distribution, Daikin plays it better. The Daikin brand products have higher pricing points that come with decent hybrid solutions (combining heat pump + furnace) better suited for extreme temperatures swing, as well as bringing in the VRF technology (the use of an inverter to vary the refrigerant amount and/or switch between heating and cooling) into the US. The Goodman brand products are replacing Carrier’s positioning by being the low-cost player that tries to dominate the entire market with mass scales and distribution reach. In general, it focuses on the less competent technicians with fewer bells and whistles, and target homeowners who appreciate lower prices. Looks like Carrier is in some trouble here.

To further understand distribution in the residential HVAC segment, let us also look into Lennox.

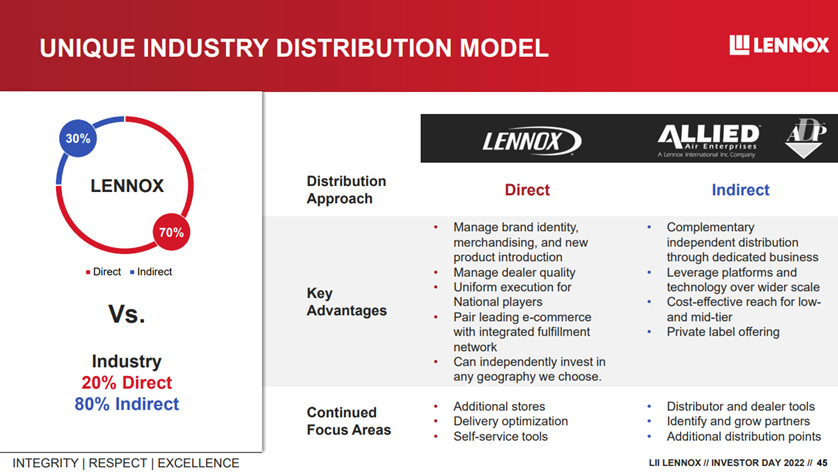

Lennox’s direct model is unique. The company was founded in 1894 by Dave Lennox, and it established the one-stop distribution model selling directly to technicians as early as 1904. Lennox only started to build its two-step distribution network with the acquisition of Armstrong in 1988. In 2000, Lennox went downstream too much and actually owned the residential servicing by acquiring Service Experts. But the residential servicing business was a mistake with only a 3% margin, it was then divested to private equity in 2013. The company rebuilt its distribution with a new PartsPlus store format. Today, Lennox has 2 main segments, residential and commercial in a 70/30 split.

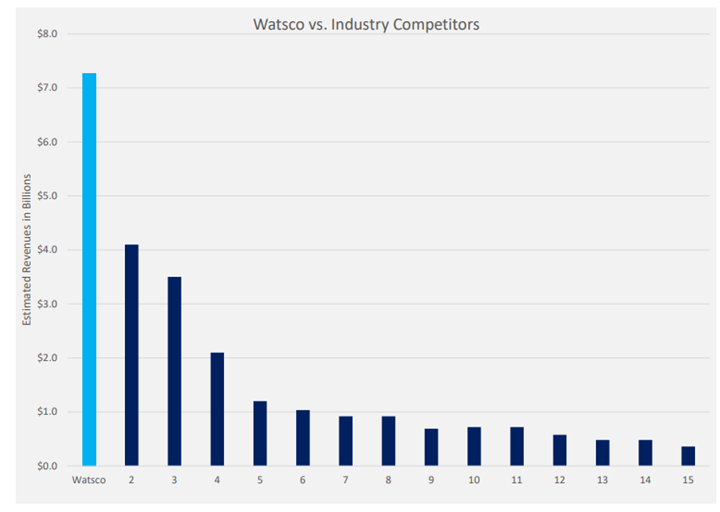

Lennox’s store location in America, from Investor Presentation 2022.

Where Carrier failed to go direct, Lennox succeeded. Lennox distributes ~70% of its residential sales directly to technicians via ~250 Lennox Stores scattered across North America. Look at the map above (red color dots), Lennox overcomes the dispersive nature by clustering many stores in large metropolitan areas (E.g. LA, Dallas, Chicago, Atlanta, Washington D.C.) where it has already built up well-integrated fulfillment networks at scales.

Lennox’s stores serve as the same-day pickup point for technicians to complete their replacement jobs as soon as possible. Many technicians are small independent local teams which do not plan inventory ahead and lack warehouse storage. Being close to technicians is important, as the proximity allows for fast delivery, where technician could take advantage of the time-sensitive nature of replacement sales and earn large profits for homeowners who can’t afford to wait. Thus, a network of distribution centers (orange color dots in the map) is also needed to strengthen inventory supply at the right time, much like how auto parts stores getting similar replenishment support from distribution centers. Lennox claims that 80% of the demand from its stores can be fulfilled by DCs on the same day.

The remaining 30% of residential sales are made through Allied Air Enterprise (blue-color dots). These are ~1K locations from independent distributors to fill the gaps of the rural places which are less densely populated. Lennox won’t touch them because mid-tier and low-tier city do not have sufficient volumes to ensure distribution cost effectiveness. This model is unlike the industry average where 20% of sales are made directly + 80% of sales done independently.

Lennox distribution strategy illustrated, from investor presentation 2022.

Lennox sells its products at factory margins to keep prices low, while having better OP margins than peers. This may seem strange at first, but there are simple reasons for it: its lack of manufacturing scale with smaller market share + higher in-house distribution costs are offset by removing distributor share of profits (e.g., Watsco GP margin is at 22%).

The company puts in extra effort to keep their technicians loyal to their brand. Apart from the standard rebates and incentives, not going to the distributors means Lennox plays the role of directly supporting technicians. Training is one. Technicians can learn how to run a contractor business directly from the brand itself, including how to sell the products to homeowners, and how to deal with sales and financing. Once the technicians are on board in the ecosystem, Lennox would push them to use its LennoxPro ecommerce channel to integrate the entire sales and marketing process, becoming an enabler for technicians to manage their business. On top of that, the App helps identify replacement units and sell parts directly. In 2021, e-commerce accounts for ~40% of sales for Lennox.

Although Lennox claims that 80% of its sales are related to replacement and repair, I found out that not all replacement sales are on an emergency basis. Based on the Q4 ’23 earnings call comments, management has hinted that emergency replacement mix accounts for ~10% of sales. This combined with the 20% mix on parts alone, implies that 50% of sales are routine replacement sales that are not supposed to be as lucrative.

The use of warranty data to anticipate sales on each replacement cycle, from Investor Presentation 2017.

Unlike Carrier, what’s more important is that Lennox distribution channels are well coordinated. To a point where the company has collected robust warranty data over the years and is looking for ways to anticipate the catastrophic failure rate on each product cycle to predict new replacement sales. I know, this kind of analysis is seen in presentation slides for almost every OEM brand, but the difference is Lennox have better data quality simply because they sell directly, with technicians are on their ecosystem instead of a distributor’s. Such coordination also minimizes outdated inventory in the markets, so Lennox tends to gain share whenever there is a new regulation, be it for minimum energy efficiency or with new refrigerants requirements.

On the idea of refrigerants regulations, check out Alex’s post on Hudson Technologies. He has unique insights on this topic – where refrigerant reclamation could be a play.

To see how channel coordination is useful: during the Q3 ’23 earnings call, management highlighted the fact that post-covid has built up an excessive inventory level where they are seeing independent distributors going through minus 20% in sales while Lennox’s own channel has only been flat. But the downside of the model is the limited market potential. Lennox remains a small player because the direct model won’t work as well outside of these major cities.

Lennox financials, from CapIQ.

Lennox’s historical performance was driven by sales expansion (via volume) + margin expansion. Looking at the numbers, there was a sales hiccup in the business during the ‘07-’09 downcycle. Homeowners were getting out of the US real estate bubble. Sales suffered from $3.7B to $2.8B in 2009, as housing needs evaporated. After the macro weakness, Lennox growth took off: PartsPlus store count went up from 62 in 2010 to 240 in 2018. These stores were renamed Lennox stores after 2019 and their focus shifted into building e-commerce sales. Topline sales growth was averaging 5% for the past 15 years prior to Covid, mostly driven by volume. This allowed for larger scales that translated into margin expansion from ~8% in 2010 to 17% in 2019. But after 2021, company margin took a drag down to 13-15% due to the commercial segment.

The commercial segment isn’t really the strength of Lennox. While some components are shared during manufacturing, the sales and distribution process are different from the residential side. Stores have no role to play as these tend to be high-touch customer relationships where Lennox goes to them instead. The commercial segment maintains a different distribution network than the residential segment. Lennox keeps the two business separate to optimize the economics of holding and turning inventory.

Looking at the numbers, the commercial segments exhibited larger variance in margin profile, especially for the refrigeration segment where customer profiles are less homogenous. The refrigeration part was a mix of businesses with very different profitability, market conditions, and growth prospects. Thus, management put in some effort to clean up the segment after 2018 by divesting the Asia, Australia, and South America units. The Refrigeration and Commercial HVAC segment was merged in 2023 into a single larger segment. The European commercial HVAC segment was sold in 2023 since management felt that they were not positioned to win there. A simpler business structure was intended so that more effort would be put into capturing market share in the emergent replacement market.

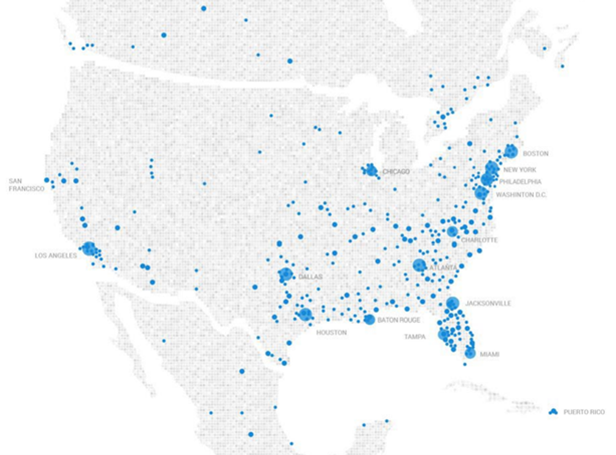

Wastco, being not the OEM but the largest HVAC distributor, will be the balancing perspective we need to question the assumption for why even invest in the OEMs when distribution seems to be the key to the thesis. Scuttleblurb and JustValue did some fantastic analysis on this company before, do check them out.

Watsco sells HVAC inventory and replacement parts to technicians who then sell it to homeowners or commercial customers. Watsco has 50% of its sales from residential HVAC equipment, 20% from commercial and refrigeration and 30% from parts and supplies. For parts and supplies, we are talking about components like compressors, coils, ductwork, etc.

Around 65% to 70% of Watsco’s sales are tied to replacement sales, where an estimated 30% share are taking advantage of the time-sensitive nature of emergency sales. Watsco has expanded distribution points from 434 locations in ‘09 to 690 locations in ’23. Similar to Lennox, many locations are strategically clustering around LA, Texas, Florida, New England, with the rest being more disperse.

Watsco Store distribution, from q4 ’23 earnings presentation.

Watsco’s scale differences, from q4 ’23 earnings presentation.

The moat of a distributor comes down to balancing superior cost structure with customer benefits.

At first, one may think distribution is just a scale game. The understanding is not wrong, just incomplete. Firstly, the picture above does show that Wastco has the largest dollar market share. This allows them to bulk purchase from HVAC OEMs, receiving generous volume rebates to scale down unit inventory acquisition costs. It is better to have one Watsco that buys from multiple brands at bulk, than having 5 smaller Watscos where each buy at smaller volumes. Often, such scales have been built up by establishing exclusive distribution rights from vendors and by rolling up smaller local players over time.

Secondly, a larger inventory volume leads to lower unit distribution costs, as the higher inventory velocity increase logistics asset utilization, and scales down logistics costs. We can check the numbers to verify the larger scale: sales per location for Watsco increased from $4m to $10m over the last 15 years. So did inventory per locations. Thirdly, the exclusive vendor relationship is also important here. Since HVAC markets are very localized in nature, the exclusive supply is negotiated on a city by city, or area by area basis.

But wait. The essence of a distributor is also about inventory management. Its role is not just storing and distributing inventory, but managing these inventories to make sure they are at the right place at the right time. Yes, the absolute scales help lower unit cost, but it is really the customer benefits that keep the pricing power of a distributor. The location proximity, speed, parts availability, and the tools used to help technicians to identify the right parts matter a lot to them. Yeah, I think I have said enough about the role of distribution in time-sensitive sales when I was analyzing the auto part stores previously.

Watsco, like Lennox, has been developing digital tools that enable technicians to turnaround jobs faster. It has increased digital penetration where ~33% of sales are made through e-commerce. Watsco’s OnCall Air App is an HVAC marketplace where it helps technicians to identify and look up similar parts (AHRI system matchups). Watsco has over 1.5m SKUs available through its digital platform, while also providing digital warranty processing, consumer literature, and selling and financing platforms. The effect is to cross-sell and upsell more parts via the platform, increasing sales penetration per customer.

How OnCall Air system matchup works, from YouTube.

One just can’t resist talking about Fastenal whenever we think about the distributor business: the company distributes many small nuts & bolts-like products required for industrial and manufacturing needs. These are parts with high weight-to-value ratios where it makes no sense for each end customer to insource it. Fastenal makes use of location proximity allowing for speedy delivery, along with strong customer knowledge to know which parts go where and at what time. So, the end results are mid-to-low inventory velocity but offsetting with higher margins. I sense that something is similar for Watsco here. It is the same killer combo of having some scale advantage combined with customer-specific knowledge (although it is much more fragmented knowledge here), plus the exclusive vendor agreement mentioned that become a significant barrier to other players to catch up.

One area of concern though, is the high 55% sales exposure of Watsco in Carrier-related product sales through joint-venture distribution agreements. These agreements provided exclusive distribution rights to Watsco on Carrier’s products, but they also increased vendor concentration of Carrier to over 65%. Likewise, 25% of Carrier sales are sold through Watsco. Carrier Enterprise I was formed in 2009 where it owns ~40% in RSI that operates 34 locations. Carrier Enterprise II was formed in 2012, relating to Northeastern US and Mexican distribution. Carrier Enterprise III was formed in 2013, relating to Canadian distribution. Simply put: the fate of Watsco is largely tied to Carrier.

Watsco pursues a “Buy-and-build” strategy where it rolls up smaller local distributors to increase sales and expand national presence. The residential HVAC distribution market is fragmented with 70% of the market in >1K players. Rather than competing head-on with these local distributors, Watsco takes advantage of the existing local customer relationships with technicians that were built over many generations. After each acquisition, Watsco provides support with aggregating purchasing scales, better vendor access, technology integration, working capital support to improve margins for them.

The company largely adopts a decentralized structure and aligns the interests of the local leaders well with proper incentives. Watsco has set up long-term Restricted Stock Plans for over 160, mostly local operating leaders who collectively own over $440m in restricted stock. Leaders usually get vested upon retirement age (i.e. cliff vesting). The long-term alignment is clear, with an average 12-year vesting period, and only 8% of stocks forfeited over 25 years. Reputation matters a lot for a serial acquirer like Watsco as previous instances of success reinforce the chance of the next acquisition by having this “win-win” industry reputation: Watsco is not just acquiring these mostly family-business to take advantage of their local relationships but also to provide solid organic growth for them. This reminds me a bit of Atlas Copco buying out local distributors. It shares the same success factor in brand reputation, a decentralized organizational structure and strong incentive alignment; albeit Atlas also innovates on products as an OEM itself.

Watsco strategy is not just on paper; the financials showed its success. Sales have grown from $64m in 1989 to $7.2B today. That’s ~110x over the last 35 years, or 14% CAGR. This includes ~69 acquisitions done to expand market reach inorganically. Since ‘10, acquisition activities have slowed down where Watsco has shifted its focus to open more branches from existing businesses and increase sales density instead. Watsco has averaged ~6% in same store sales growth since ‘10, with only 2 years in negative comp. The chart below shows that sales density per location increased from $6m (~500 locations) to >$10m (~700 locations) for the last 14 years. This is a market where winners become better. The larger scale benefited Watsco in lower cost structure, the technician integration and customer benefits ensure that cost savings were not evaporated through pricing. GP margins hovered around 24-27% while OP margin improved from 6% in ‘09 to 11% in ‘23.

Sales density chart, from Watco’s financials. Unit in $m.

Apart from OEMs (Carrier, Trane), Watsco’s competitive peers are Johnstone (~460 branches), Ferguson (~270 branches), Winsupply (~620 locations), Hajoca (~400 locations), and many other smaller independent distributors that are localized. There is a scale difference between all these major players and smaller distributors, so a roll-up strategy is equally beneficial for all of them.

But the volume per branch difference among the top 5 players isn’t as significant as I thought it would be. Let’s look at the listed co Ferguson as an example: Its HVAC revenue of ~$3.3B over its 270 HVAC branches gives us ~$12m per branch that is higher than Watsco’s ~$10m. Going back to ’21, Ferguson’s HVAC sales were only ~$2B; Removing the ~30 acquired branches that came alongside the acquisitions of Guarino, Airefco and S.G. Torrice, the sales were only $8m/branch then. Looking at the aggressive acquisition into plumbing distributors, I attribute the rise in sales density to the company’s dual-trade strategy where it appeals to contractors who perform plumbing and HVAC services at the same time. Per branch sales volume is good for distribution cost scaling, but vendor scales come from a larger absolute dollar amount. Watsco’s total sales of $7B are still 2x Ferguson’s HVAC sales (not to mention Carrier gives huge rebates to Watsco due to the sheer volume).

The key difference between the two firms comes down to the focus and level of customer service. Watsco has built a comprehensive model to bring higher sales specifically to HVAC-focused contractors. With $30B sales, Ferguson is still one of the largest building product distributors, but its resources are diluted into other business areas such as plumbing, lights, security, etc. Half of its sales are in commercial segments. Only 11% of Ferguson’s sales are in HVAC. While Watsco is the one-stop shop for HVAC, Ferguson is the one-stop shop for building products. I am not saying that Furgeson is a bad business, just that it does not fundamentally compete for the same types of customers as Watsco is serving. At the end of the day, the HVAC market is large and fragmented enough for both to grow. But as an investor, I am more confident in Watsco’s ability to carry out its simpler strategy, and I think it has better quality on the customer service front. Also, I don’t really understand the other 90% of the stuff that comes along with Ferguson anyway.

Let’s shift gear to talk about the commercial space. I am referring to HVAC used in factories, industrial buildings, hospitals, biopharmas and data centers. These are huge pieces of machines like chillers, air handlers, liquid cooling solutions. A chiller works by the same basic principle as the refrigeration cycle mentioned at the start of this article. But instead of using fans to blow the heat/cold out, water or other liquid is used to transfer heat/cold (the name “chiller” comes from the chilled liquid used to cool other parts).

For example, hospitals use chillers to keep life-saving equipment running, keep medical samples cool and maintain low temperature on patients’ body; data centers generate a lot of heat that needs to be constantly cooled using liquid cooling.

York (Johnson Control) Chiller, from Wikimedia.

Heavy and commercial HVAC differ in terms of the level of power (light is up to 25 tons capacity) and system complexity. Heavy commercial products are also known as applied equipment. They have a direct impact on the quality of a factory or a data center and are often deemed mission-critical components. The higher level of power also means the equipment is very energy intensive. A general rule of them for something like a large piece of chiller equipment is that the total cost of ownership is broken down to 10% equipment, 10% service, and 80% energy cost.

Bespoke. That’s the keyword for heavy equipment. The equipment is not meant to be mass manufactured but custom-made for each customer. The design of the equipment matters a lot more now that energy efficiency is the priority. Buying a less efficient piece of equipment does not just hurt end customer in wasteful upfront capex, but in higher opex while in operation that is more painful. Knowing this idea is important to understanding the sales process.

The heavy commercial HVAC business is driven more by direct relationship between the OEMs and end customers. The sales process involves multiple stakeholders. We have the building owner/manager, architects, mechanical contractors (mechanical engineers), or even specific HVAC contractors. Who the OEM or distributor talks to depends on the type of job it is. First is design and build job. This is where design and construction are done by the same mechanical contractor. The contractor often selects and sticks to the same provider throughout the construction. Second is plan and spec job. This is where the building owner hires a mechanical design team to come up with a general solution plan first, such as the main components needed and the key requirements. The plan is then passed to the spec rep where he puts the project into a competitive bid. The selection criteria, as far as I see, is more relationship-driven for the first case, and more price-driven for the second case. And again, all this complicated process is just to ensure that building owners not only get the best bang for the buck, but more importantly getting the equipment that fits most perfectly with the specific building requirements. In fact, in either case, it all comes down to the perceived reputation and technical capabilities of OEMs. That’s how these OEMs convince customers in the sales pitch (or in an RFP submission).

Trane’s key value proposition fits exactly that – a superior brand for higher product quality. The products are durable with a long lifespan, and often highly energy efficient. The way that it sells itself is that customers pay a hefty price tag upfront to get 2x in equipment lifespan and higher energy cost savings. But the cherry on the cake is the razorblade - the servicing business. Trane’s service GP margin is 40% compared to Carrier’s at 30%. The servicing sales are about 1/3 of total revenue and are almost half of the commercial segment (commercial is about 60% of total). In other words, HVAC servicing is almost entirely on commercial segment, unlike residential where contractors do all the servicing. Trane servicing edge comes from its ability to instrument equipment data well, reduce downtime, optimize energy use, and provide monitoring, and preventive maintenance. Although on the data front itself, I think Johnson Control is still ahead of them.

But let’s go back to the sales process again because this is where Trane gets interesting. It turns out that corporate culture and incentives matter a lot. The sales guy in an OEM firm is also known as a manufacturing sale rep. Salespeople are the lifeblood of a commercial HVAC company. Trane’s trick is having decent salespeople that are good at working with engineers on the customer-side to convince them to have Trane’s equipment included in their specifications. The sales rep goes out his way to build this relationship, and even does the design work for them and sends the CAD file over to show that Trane equipment would fit. In some regions, such as Florida, the share of mechanical engineers who are pro-Trane can be as much as 80%. Trane’s Florida unit gives the right incentives to the manufacturing sales rep to go out there and push for its products.

Yeah, but Trane’s residential (40% of sales) is a meh. Brand strength is not as strong as its equipment is priced higher than peers. Again, the residential market tends to be more price competitive with standardized design.

Johnson Control is another powerhouse when it comes to heavy commercial HVAC equipment. Similar to Trane, it too aims to make more money back using servicing (~30-40% of sales). A general rule of thumb, again this is not meant to be accurate, is to generate about $5-7 of lifetime value from each $1 of asset sold, from value-added services. The equipment may have crappy margins, but the software and servicing have upwards of 30% margins. Servicing pricing is tied to asset optimization and improved productivity.

Johnson Control’s competitive advantage is its data and connectivity. Johnson collects vast amounts of customer-specific data translating to better down-time modeling and serviceability. For instance, a chiller would produce over 100 different data points from each customer. Similar to elevators, these calculations also help optimize routes for technician servicing and prepare parts replacement beforehand. Johnson also sells extended warranties, essentially a form of performance guarantee, where they are also very lucrative. Over the long-term, what matters more is the reputation and specific customer knowledge (i.e. customer data) of the previous product cycle translating to the success on the bidding for the next replacement unit, stretching out the customer lifetime value yet again for another 30 years.

Coming back to Carrier’s commercial, the company has way too messy sales and distribution channels and that has led to some internal channel conflicts. Carrier sells directly to commercial customers via its Direct Sales Office and performs servicing over in-house branches. Local value-adding distributors also buy from Carrier manufacturer sales rep, and face competition from Carrier itself, and often enter price wars to win the servicing contracts. For heavy commercial market, Carrier’s presence is rather weak. Its market share is ranked #4 after Trane, Johnson and Daikin. Trane and Johnson have been the ones gaining commercial shares over Carrier over recent years.

Market share of light (left) commercial market vs heavy (right) commercial market, from BofA Carrier initiation report.

This is a good segue to come back to the light commercial HVAC market. This is also known as the unitary market. Unitary refers to a centralized HVAC system for a commercial building where air flows through air ducts to reach the building users. So, these are also known as rooftop units (RTUs), because they are often installed on the rooftop that supports the rest of the building. Light commercial market is very similar to residential markets, but the market size is less than half (residential’s ~$13B vs light com ~$5B). I think the lack of a sizable scale and production cost advantage + price competitive bidding process means this is likely to be the least profitable segment of the three.

Commercial Rooftop HVAC units, from here.

Nonetheless, to make things interesting, I am going to walk you through the last company, AAON, which uses a unique strategy to win in this space.

AAON sells entirely to commercial customers, with ~70% of its sales are in rooftop HVAC units. This has been the bread and butter for the company. These RTUs have better features and are usually better customized than what the market offers. Another 20% are from semi-customized condensing units, air-handler, water-sourced heat pumps, and other HVAC parts and components. The last 10% is on higher-end data center and healthcare cooling solutions, under the name of BASX solution.

AAON’s strategy has 3 elements:

1. Building standardized premium components with customized design.

2. Optimizing production and asset efficiency with planned replacement units.

3. Winning customer with highly incentivized manufacturer sales reps.

First, AAON offers semi-customized HVAC where it uses standardized parts but customized design. This semi-customization is leveraging on computer-aided manufacturing systems to allow for wider product breadth and variety, which makes AAON easy to suits unique customer’s needs. At the same time, the company uses mass standardization of premium components to scale down parts procurement costs, and combining with a build-to-order model that simplifies inventory management. The trick is just about having customization + scales at the same time.

AAON often commands a ~20% pricing gap over peers with premium branding. This quality premium is justified by high energy efficiency, longer lifespan, ease of serviceability and lower maintenance effort. AAON is very conscious about protecting margins. It targets customers that demand high performance and durability. This is why the company does not have much market share with National Accounts like restaurants and retail chains, who have more bargaining power and often go for low-priced options. This essentially limits its growth to the most profitable light commercial customers. To put it simply, AAON’s products are over-engineered to a point where they exceed all customer expectations yet come with only a moderately high price tag.

Second, AAON optimizes its production by 1) running an asset-light model and 2) having manufacturing flexibility. About 65% of AAON’s sales are planned replacement units. AAON uses a build to order model. The order lead time is around 11 weeks or less, and the company only starts procurement and production upon receiving request from customers. AAON holds minimum inventory and seldom runs into channel issues. In contrast, residential HVAC OEMs have 6-7 months ahead to start building inventory. The following table illustrates what I am trying to say: AAON seems to strike a good balance between having a decent 19% OP margin, but yet does not hold as much inventory (28% of IC compared to Daikin and Lennox). However, despite also not having the goodwill drag as Lennox (both are organic growth companies), AAON’s IC turn is much lower because of all the capital investment it has made in recent years to expand its operations. We’ll come back to this later.

AAON’s financials compared to peers, numbers from CapIQ and annual reports.

To protect manufacturing margin, the manufacturing line must be flexible. Customized design implies more line-switching activities, a significant cost that must be well planned and be absorbed by customers. Backlog driven business may seem to have strong order visibility, but still subjected to general cyclical capex trends from commercial segments. From its annual reports, we see in ’13, ’18 and ’21 GP margins faced severe decline, with material costs and manufacturing efficiencies cited as key reasons. The cost pass-through is not always 100%.

But the good news is AAON has strong pricing discipline even during downturns. For commercials, pricing does become a larger factor during downturn; the impact is uneven depending on customer profile. AAON targets customers who pay for premium products, and typically are more resilient to downturn as well. Think of schools and government buildings with deep pockets. The replacement market is where AAON shines, the company admits that it is at a competitive disadvantage when it comes to new construction.

Third, AAON has a strong sales force and motivates them with generous incentives. AAON has ~80 salespeople and ~60 independent manufacturer sales reps’ organizations. Like the heavy commercial market, the sales process is relationship driven. At best, the salesmen deal directly with building designers and owners, convincing them to push for AAON products for better quality. If that is not possible, they would avoid more price-conscious HVAC engineers and convince the right contractors who value performance and durability. AAON’s customizability often becomes a weapon for these sales reps to sell. They always have room for negotiation on specific customer requirements, knowing that AAON would back them up with a wider catalogue and product breadth. Sales reps also play a role to quickly patch a customer relationship stained by quality issues. They take good care of end customers, so AAON brand image is protected.

If you want to meet a rich person, meet an AAON salesperson or independent sales rep. Typically, a manufacturer sales rep, such as Long Building, buys from AAON and generates a good 20% markup by reselling it to end customers. AAON is pressuring these sales reps to put in effort all the time, switching out old ones with more productive ones, almost like a McDonald’s franchise agreement. I am not sure if the distributor agreement is exclusive, but since AAON’s products are often the #1 or #2 best-selling ones among independent manufacturers sales reps, my guess is that they have developed specific processes and have grown used to selling AAON’s products. After all, they make a ton of profits selling them. The performance-driven culture and incentive alignment is permeated throughout the firm. AAON provides decent salaries (its median income is at $61K, compared to $51K for Carrier and $68K for Trane’s) to its employees, and has a profit-sharing scheme where it distributes ~10% of its pre-tax profits to eligible employees.

AAON’s volume is small. Its current sales are only $1.2B compared to the behemoths mentioned earlier. Despite the more cyclical customer profile and volatile sales growth, AAON has had decent growth and is rather profitable. First, its return on capital has been around 20-30%. Second, average growth prior to Covid boost was ~5%, GP margins moved around 20-30% and so did OP margins between 12-17%. Nonetheless, this translated into a decent 20% compounded returns over the last 10 years for its stock.

I want to stress that a) the company-reported share in >5-ton rooftop market has not moved past the 10-15% range, b) organic growth was mostly in unit volume and not much on price, c) there were no major acquisitions until one recently. Putting the 3 clues together, I inferred that the company growth was mostly attributed to market volume growth, which is the key message of the company. AAON itself represents a niche market alone (I haven’t seen anyone else do what they do), and they are saying that this niche would expand into more customer reach.

AAON market sizing illustrated, from investor presentation 2022.

Bears would point out AAON’s weaknesses with its low FCF margin resulting from its high capex and limited market size. The two issues are connected. High capex is required to invest in manufacturing facilities that expands AAON’s market reach. The company never really had much scale to begin with as it prioritized the most profitable part of light commercial customers. It is not good at handling national accounts and sees them as low-margin customers that are not worth the effort. Seeing that this attitude has not changed, I can see why there is a TAM size concern in the light commercial space. This semi-customization model doesn’t appeal to that many customers. After all, product innovation here is somewhat over; AAON is just doing process innovations. They use more flexible and faster manufacturing lines and have more efficient quality control procedures. There has not been much product breakthrough for the company, and AAON has been falling behind in terms of compressor technology and high-efficient gas heating.

AAON’s capital allocation, indicating that more capex over dividends and buybacks in coming years to expand into new segments.

AAON market sizing illustrated, from investor presentation 2022.

To address this, management is looking to expand its presence to other light and heavy commercial businesses. This is where the remaining 10% of its sales are about, they include bespoke (fully customized) cooling solutions, air handlers and condensing units. The company acquired Basx Solution in 2021 to go into data centers and healthcare customers, competing against the likes of Vertiv, Stulz, and Nortek. The deal was priced at 100m + 80m earned out, or about 4x segment EBIT in 2023.

I thought of doing a whole bunch of analysis on this new segment and tried to come up with some insights to it. The truth is, at this point I am just speculating. The customized market does have a larger TAM, but I don’t see why the other competitors in this landscape can’t do as well in offering such customized solutions as AAON. Requirement is much tougher, and semi-customization is not enough. There is no moat for AAON here in terms of its distribution channel or customer connection. The incremental return in this space is going to be much lower than its light commercial units.

There we have it. We ran through the 4 main companies. Let’s do a high-level recap on each company:

Carrier relies on a vast network of 3rd-party distributors to provide a nationwide presence. Over 75% of its HVAC business is replacement sales. Its products are priced cheaper, but it utilizes large manufacturing and distribution scales to achieve cost advantage. The catalyst is really about management cleaning up the business segments and regaining lost positioning from Daikin and Trane on HVAC segment, by aligning the distribution channels and keeping up with product offerings.

Lennox bypasses these distributors with its direct distribution strategy with 70% direct sales to contractors. It has a stronger focus on the residential side compared to the rest. The lack of distribution layers also means Lennox gives OEM pricing to contractors, while streamlining distribution costs by clustering stores in high density cities. Upcoming regulatory changes in equipment standards are tailwinds for the firm; it will gain a few shares, but I won’t place a high growth on the firm.

Watsco, being closer to the customers, takes advantage of the time-sensitive replacement sales by providing inventory availability and service to the contractors. The long-term growth driver would be that it continues to roll-up smaller fragmented independent local distributors, where it continues to eat up the 70% share.

AAON sells semi-customizable commercial units with over 20% pricing premium. Returns are good because: 1) The order-to-build model allows for production planning enhances margins and minimizes inventory needs, 2) 65% of sales coming from planned replacement needs that are highly predictable, and 3) a fantastic performance-driven sales force and corporate culture. The growth driver will come from the expansions into heavy commercial like healthcare and data centers.

Among the four, I find Watsco’s business model to be the most attractive, followed by Lennox and AAON, and lastly Carrier. This is funny because of how intertwined Watsco and Carrier success factors are, given that they have entered into so many distribution partnerships. My reason is simple: I think ultimately this industry comes down to who owns the technicians and who has better customer relationship.

It is better to bet on the largest distributor guys in the residential space and bet on the OEMs with the best relationships in the commercial space. Watsco seems like an easy choice for capital allocation if not for its high valuation (~30x P/E) and high Carrier sales exposure. Lennox and AAON have unique and high-quality business, but I have more trouble pinning down growth comparatively because of the unique business model that gives me a limited TAM (and my limited mindset, of course).

Nonetheless, let’s put them through the valuation tests.

First to rule out is AAON. Even if I put in a 10% growth in topline while keeping margin at 16% (keep in mind this company will be heavily expanding), a 30x 5-year exit multiple gives me 3% IRR. So, next.

For Carrier, valuing it won’t make sense unless I am okay with the assumption of a sensible management to clean up its business. I put 6% growth + 0.5% margin expansion (starting from 15%). Exiting at 20x gives me 8% IRR. But let’s say Carrier gets re-rated to 25x, IRR would have been 12%.

For Lennox, its business quality is quite high, so I think putting 25x seems a fair multiple. Fine, let’s just take management guidance, for argument’s sake. I would put around 5-6% for growth and margin expansion to 20%, but even that only gives me around 9% IRR.

For Watsco, there’s no reason not to follow its historical average of MSD organic growth + 1-2% inorganic growth, that gives us an optimistic case of 7% growth. Let’s also assume 0.5% margin expansion just from larger size distributor cost scaling. Putting in a 24x exit multiple, it gives me 12% IRR, falling short of the historical 15% IRR because valuation is high + I don’t want to go too wild with acquisition assumptions.

Yeah, all these “short-term” 5-year financial estimation don’t give them a fair case because HVAC would have such a long runway due to its replacement sales and stable market structure. With 2020 hindsight, if you go back 10-20 years ago, not investing in either of the 3 would each have been a mistake. I hate to say this, but if I must close one eye on valuation and just buy one today, I’d probably still pick Watsco given how timeless its model is. Ideally, given the disperse nature of residential HVAC, the best case is that I don’t have to bet which OEM wins if I can just bet on a distributor that is able to switch among OEMs.