Many of us use elevators every day, but few know that the elevators business is a cash cow with immense profits: OTIS, Kone and Schindler make at least 20% pretax return on capital each. I like the elevator business because of its razor/razorblade business model. The new elevator installation is the razor with only 7% OP margins to lock customers down in a stream of razorblade-like maintenance services and parts replacement subsequently earning 20% OP margins. Elevators are mandated to be routinely serviced by regulation and safety concerns. Hence this servicing business, often based on multi-year maintenance contracts, translates into a sticky, non-cyclical revenue stream with a high contract renewal rate. Switching cost is high, as pricing power is realistically capped by the high disruptive cost of a failed elevator. The new equipment market is stable and consolidated, but the servicing business is more fragmented. Besides peer competition, Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEMs) face threats from local third-party independent service providers (ISPs) taking share in the aftermarket servicing business. Therefore, I try flipping the argument around and ask why not bet on ISPs instead (e.g. Japan Elevator Services). This is analogous to the idea where car manufacturers (known as auto OEMs) do not make much money from selling cars to new buyers (surprise, surprise!), but from selling car parts and financing to people who already own a car. But car owners switch to visiting cheaper independent car body shops over going to car dealers and getting the OEM parts instead. In my Auto Parts Retailers Post, I was arguing to bet on these third-party aftermarket auto parts businesses over auto OEMs, so why is elevator OEMs different here?

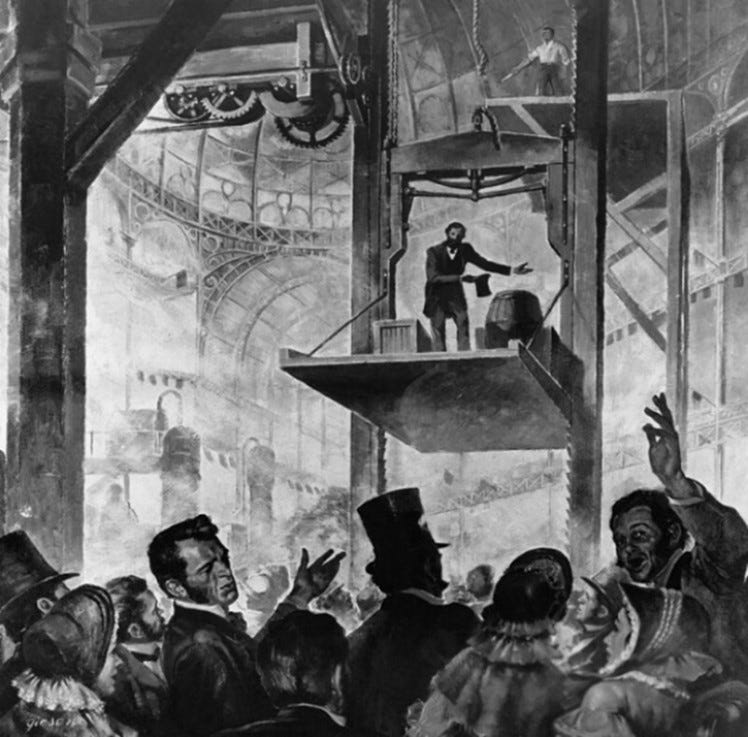

OTIS Worldwide is the largest and the most well-known elevator company in the world, founded by Elisha Otis in 1853. In the past, elevators were thought to be unsafe to carry human, until Elisha Otis invented a safety lock mechanism preventing passengers’ death from broken ropes. In a very charismatic fashion, Otis held public demonstrations in New York where he stood inside the elevator and ordered someone to cut off the rope. The crowd was amazed that the elevators came to a halt after falling only a few inches, and the OTIS brand has been synonymous with elevator safety ever since. The weak market conditions in the 1970s allowed United Technology (UTC), ran by Harry Gray, to pursue a hostile takeover of OTIS and diversified UTC out of its underperforming aircraft business. Gary saw the profitability and niche technology of the elevator markets and used OTIS as a gateway to shift UTC’s exposure from government contract sales towards commercial and residential businesses. Well, the funny thing is that OTIS was certainly a useful earning boost for UTC, but Gray later admitted that he didn’t know how UTC could help in strengthening OTIS’ business profile. But being part of a larger conglomerate did give OTIS the balance sheet and talent by parachuting UTC executives with M&A experience to go on an acquisition spree and expand overseas. During 2010s, UTC’s segment breakdown showed that OTIS was the carry of the team, offering 20-30% segment return on assets vs Carrier’s at 10-15%, and the capital-intensive Aerospace segments at only 5-6%. Despite having the highest return, the OTIS segment had the classic tradeoff of high profitability and lack of growth. Management finally wised up in 2018 to split UTC back into 3 distinct units, so the elevator segment could be better managed independently while the aerospace business was then merged to form RTX. Hence, we have OTIS listed as a pure play company now.

Elisha Otis’ public demonstration of his proprietary safety mechanism, picture from Wikimedia.

OTIS sold ~160-170K units in 2023 with a blended ASP of around $38K per unit. Most of them are replacement units on existing buildings. The company has a maintenance base of 2.3 million elevators, with average servicing revenue of ~$3.7K/unit as of FY23. New equipment sales (~40% of sales) earn 17% GP margins and 7% OP margins, while servicing (~60% revenue) earn 38% GP margins and 21% OP margins. The purpose of the new equipment sales is to convert them into the maintenance portfolio and make more money from servicing. OTIS has a global conversion rate of 65%, with conversion rate hitting 90% in Developed Markets (DM) but only at 50% in China and other Emerging Markets (EM). OTIS has 1/3 split on its sales between America (US being the primary, obviously), EMEA, and APAC (with China being 17%). But EMEA has the largest maintenance base with 1/2 share (1.1 mil), and Americas and APAC each has 1/4 share (17% in China). OTIS reported a 93% retention rate recently, and that is mostly stemming from the stickier EMEA & America maintenance base. Since elevator is such as globalized business, change in exchange rate often drives the sales growth more than the organic growth. In this case, OTIS’ maintenance servicing revenue from Europe (part of EMEA) can have a big sales impact if EUR / USD depreciates a lot.

OTIS’ organic sales growth had stayed at LSD coming into the early 2010s, with growth only coming from replacement sales of existing buildings, but servicing margins had all along been above peers because management was very disciplined in pricing strategies. While the global maintenance base started to grow massively since 2012 because of this China residential boom, OTIS’ market share suffered from 18% to 14% despite unit sales remains the same. OTIS missed out a big portion of growth coming from China because the culture was obsessed with maintaining margins when OTIS was part of UTC. Management incentives were solely based on profitability and did not see the point of pursing growth. As OTIS was about to be spun off as an independent unit, incentive structure changed to include organic growth as a target. The new management had to ramp up OTIS’ China presence to protect market shares along with profits. As expected, GP margins fell from 30% to 20% despite unit sales going up from 130K to 160-180K (new equipment shares went back up to 20%), and organic growth has come back to HSD. More importantly, since OTIS is no longer just selling replacement units, the maintenance base has finally inched up from 2 million in 2017 to 2.3 million in 2023.

Like auto production process, many elevator parts are manufactured by suppliers, with OEMs making core parts like motors, electrification systems, and other proprietary components. OEM merely assembled them and slaps a label on top of it. But unlike car OEMs, the parts are shipped to construction sites where an elevator OEM assembles it there. This explains why elevator OEMs carry little inventory (16-40 days) and do not require much manufacturing space, maintaining high PPE turnovers (9-12x) compared to other heavy equipment industries. On top of that, contract liabilities/advanced payment is the largest line item under current liabilities for OTIS & Schindler (Kone’s is #2), as customers fork out cash upfront for OEMs to purchase components, further lowering IC needs.

Comparison of inventory and PPE across different heavy equipment industries, data from CapIQ. *Inventory days are calculated based on sales instead of COGS.

Elevator vendors are assessed on technical capabilities (speed, levels built, capacity, space usage), reputation (special product tech/features, installation quality, project execution / completion), delivery time and pricing. But elevator OEMs are dealing with architectures and general contractors on top of end customers. In low and midrise residential buildings (i.e. below 10 floors), the general contractors have more power to make decisions on vendor sourcing. They are less impressed about the premium elevator features as long as the machine meets the intent of the specifications. Their KPIs are cost-focused, so pricing plays a larger role. OEMs offer commoditized elevators with more standardized designs to minimize costs. For high-rise (i.e. 10 floors and above) commercial buildings, end customers have more influence on greenlighting the right vendors. The barrier to entry into this space is never about capital intensity but more so on customer & supplier access. The reason why the market for new equipment is dominated by top players is because only these top players could provide safety and quality assurance upon installing their own products.

Both the sales process and construction process are lengthy, so you don’t want to risk giving the project to some random new entrants, or risk delaying the opening of the buildings. Elevators contracts are awarded at least 2 years before the building opens, with revenue recognized upon stages of equipment completion (so-called “milestone” approach). That’s why elevators OEMs not just show current revenue (that were driven by orders coming in 1-2 years ago), but also new order bookings and current backlog. You know, I once made the mistake of associating order backlog with sales. The quality of future sales is subject to the likelihood/ability from customers to cancel future orders (overproduction issue), and the ability for OEMs include cost escalation clauses in the contracts (input cost inflation issue). The reason for equipment margin fluctuation comes down to the upfront fixed price awarded in the contracts being mismatched with higher subsequent cost, be it fixed or variable. So, orderbook driven businesses protect themselves on the margin front by either stocking long shelf-life inventory with low obsolescence costs (e.g. Texas Instruments) or in the case of elevators, using an outsourced procurement model + robust supplier network to flex the material/component cost well. Here, unlike what I found in my Solar Inverter post, the bargaining power is with the brand owners because supply side is much more fragmented (Kone has ~2K material/component suppliers; OTIS relies on 500 key suppliers), and upstream players rely upon the same 6 global OEMs to give them volume. Over the past 1-2 decades, major elevator brands took advantage of global supply chains1, and standardized parts/component production processes. For OTIS, the low and mid-rise building elevators use cheap components made within its US plants. Elevators in high-rise building with sophisticated design source components from China, Mexico, and Spain instead. But the downside of global sourcing is that it adds to the risk of exchange rate fluctuation.

In America, the material/labor share is a 60/40 split in equipment production cost. During Installation, the powerful unions give workers a lot of bargaining power. OTIS outsources some of its installation labor to third-party firms where it only inspects the quality upon completion. But that doesn’t lower costs, since workers come from the same multiemployer union (e.g., IUEC) anyway. Elevator technician is one of the best-paying blue-collar jobs in the US, with wages up to $50-60/hour. Since unit labor cost is hard to control, worker productivity and installation process efficiency become important. During upcycles, OEMs would keep some amount of backlog in the future to digest to maintain more uniformed installer labor utilization rates, and keep equipment margins stable. Margins only start to suffer 1-2 years after old backlogs are cleared while weak macro or market positions are not enough to replenish new orders into deliveries, spreading the fixed cost base over small outputs. Quality labor is hard to find due to certification issues and strong unions, so firing is only a last resort.

OTIS’ strengths lie on the equipment side and the brand is well recognized in North America and Europe, with the largest maintenance base for both. The consensus view among customers is that OTIS elevators are technically superior and well-built. The control systems are reliable, the components are durable, and accidents are rare. The elevators’ lifespan is often longer, with less breakdowns and more uptime. OTIS outperforms peers in MR conventional traction elevators2, but Kone makes better MRL traction elevators with a lot of innovations. In recent years, OTIS has responded to digitalization demand by offering more connected units (elevators linked to online servers) with built in IoT (internet of things) features. Such IoT are predictive maintenance, smart energy management, remote diagnosis, and building management software integration. These smart features are enabled by subscribing to OTIS ONE maintenance package. Out of the 2.3 million maintenance base, 900K are connected and 500K are under OTIS ONE services. So, OTIS is good with technical aspects, and it has the world’s largest maintenance base embedded with digital features. OTIS’ market positioning is weak in China. Being the #4 player, OTIS is not as flexible and competitive as Kone and other Japanese players (Mitsubishi, Hitachi Toshiba, and Fujitec). It has 2 main issues to address: 1) sloppiness in managing local distribution channels where sales agents are not trained and incentivized well enough to push for OTIS’ products, and 2) poor local partnership (In China, you have to invest along with a local partner) and the lack of oversight that allows the partner to slowly eat up OTIS’ share by pushing their own products instead.

Kone’s expansion history followed the classic domestic-Europe-US-EM track, a common recipe for European firms. It went through phase 1 in domestic focus and war (1910-1950), phase 2 in using M&As to expand in other DMs and build relationships for maintenance base (1950-2000), and phase 3 by organically capturing EM growths via tech edges and partnerships/alliances (post late-1990s). Not many significant events happened until phase 2 & 3, so I go straight to the important years. During the 1980s, Kone went overboard to invest in R&D and diversified into escalators, medtech, wood, paper, and suffered from intense competition during the early 1990s. The business was streamlined back into an Escalators & Elevator pure play firm in that decade. Phase 2 was key for Kone to build up product technical capabilities on larger customers. It laid the foundations for Kone, at the turn of the century, to shift its growth strategy into EMs.

Kone sales expanded from ~$3B in 2003 to ~$12B in 2023, with Asia Pac contribution going up 3x from 13% to 40%. Obviously, Kone was not immune to the declining margins from its incremental China sales, with GP margins dropping from 26% in 2008 to 20% now. Reason is Kone’s 160-170K unit sales in 2023 came with 2/3 (~120K) of Chinese units that has about 50% lower in new equipment ASP (~$25K) compared to the rest of the world (~$50K). As a result, Kone has a few thousand dollars in its blended ASP gap compared to OTIS. It has a ~5-7% OP margin gap below OTIS on its new equipment sales. Despite Kone matches in new equipment units, its dollar sales are below OTIS. But the company has a long-term plan. New conversions did the trick of building up Kone’s maintenance base from ~850K to ~1.6 mil now, and the company waits for them to age like wines to increase per unit service revenue in the future.

Kone’s presence in China is faced with competition coming from Japanese electronics firms and local competitors. China is important. Its market sales of new equipment units account for about 2/3 of global units. Installed base in China is 9 million units, or 40% of global maintenance base. There was a huge runway in unit sales after the turn of the century into mid-2010s, driven by a combination of a boom of residential floor space along with higher elevator intensity3, the number went up from 250K in 2009 to 600K in 2014. But annual sales unit plateaued in 2014 and now hovers around 600-700K4. Since the new growth was recent, the age of the maintenance base is young with over 95% built within the last 20 years. China’s new equipment market share has a 70/30 split between foreign and domestic brands, where foreign brands are recognized for better technical capabilities while most local players compete on pricing. The 30% local share is then further split among 600-700 Chinese brands, with Shanghai Mechanical leading as the local premium brand with 90K units sold globally at ~27K ASP, and Canny Elevator as a typical low-price brand with 35K units sold at ~$11K ASP.

China aftermarket competition, from Kone’s Investor Presentation in 2022

Among the foreign brands, Kone (~18% share) is the market leader with 100-120K units sold in China annually under its GiantKone and Kone brands. Next two largest are Japanese firms Hitachi and Mitsubishi with similar shares (~15%) and units but are conglomerates each with elevators taking only ~10/20% of company sales. OTIS ranks #4 with ~80K units sold, followed by Schindler and TK elevators as distant #5/6. Product quality-wise, all top 6 foreign brands are seen as better than Chinese brands, but sales in China market is heavily driven by distributors. The foreign brands ranking #4-6 are results of poor distributor network quality and execution. Even the top players aren’t leading by that far. Kone’s cumulative conversion rate (current base / all units sold by far) has only been 40% in China, so despite being the largest player, Kone has only half a million units under maintenance base out of the 9 million total.

Stronger equipment sales and lower service ASP (younger maintenance base and lax regulation) means servicing is only 20% of China’s market size compared to 2/3 in DMs. So Kone’s China service ASP at ~$1K is not even 1/5 compared to the rest of the world, because China is plagued with 70% share from competitive local servicing firms (non-OEMs) waging price wars. Even among OEMs, Kone’s service ASP is still 20% lower than OTIS’s ASP at ~$1.2K. I suspect it is because the base is blended with more low-value mid-rise residential buildings. Even if service margins are comparable since labor cost is much lower here, dollar profits are still way lower, and hence smaller profit pool contribution. Kone and OTIS are trying to capture shares from larger property developers5. This is good for foreign brands. Not only do large property developers have larger budgets for more sophisticated elevator designs, but they have more stringent safety requirements and are likely to require nationwide coverage. Compared to OTIS, Kone had been better at choosing the right cities to invest in China. The brand is perceived to be safer since it had fewer negative headlines.

Comparison of ASP between China and the Rest of the World, most data compiled from official sources, equipment units are based on market share estimates.

There are broadly speaking 3 types of elevator servicing offered by an OEM: repair, maintenance, and modernization. The lifetime value of an elevator extends beyond the initial purchase price. First is offering new equipment, then customers are converted into long-term servicing contract, once the equipment reaches 5-10 years, field engineers would start to suggest parts replacement and component upgrades. When the equipment ages past 15 years, it is old enough that OEM would start to pitch for major overhaul / brand-new equipment to keep up with new technology, selling the idea of cost efficiency (Kone claims up to 70% cost saving after a modernization project) and lower failure rates. The cycle rinse and repeat. For illustration, I made the following charts to illustrate how the cash inflows look like over 1 cycle using some made-up figures.

What hypothetically cash flows look like from the OEM point of view, self-made with rough assumptions.

First is repair. Sales visibility and profitability have an inverse relationship. So, the least visible repair business has the most profits. When an elevator breaks down, its inconvenience makes it unavoidable for servicing partner to charge high prices. It is a time-sensitive business (24/7 standby repair services), and the aftermarket spare parts are sold at high prices at the site of the repair. But repair is often bundled into the maintenance contracts.

Next is maintenance. Sales visibility is strong, but the margins are still decent due to pricing power resulting from a high switching cost. Since elevator maintenance cost accounts for merely ~3% of the building’s operating budget, it is not worth the effort to look for another servicing partner and save a miniscule amount of budget. Routine maintenance is mandated by law in many cities to ensure elevator safety. The frequency of visit depends on the types of elevators and regions. For example, New York City requires elevators with door lock monitoring, lighting efficiency and power regeneration (energy recycling) while California mandates more earthquake-prone features (seismic elements). OEMs offer the first year of maintenance service for free as warranty. After that, customers renew contracts based on 3-5 years interval. These contracts are often embedded with built-in price increment and auto-renewal terms. The basic pricing strategy in these maintenance contracts works like an insurance contract. A higher tier plan that comes with better coverage would require larger annual payments, but customers have a lower chance of incurring additional charges when something goes wrong. OTIS tiers its offering from the basic Lubricate & Survey package (~$1.8K/year) with only periodic survey, to the full OTIS maintenance contract (~$3.5K/year) with preventive maintenance, parts coverage, safety test, and access to immediate service call.

Last is modernization. It accounts for about 30/40% of service revenue for Kone/OTIS. Many major upgrade projects take weeks to months to complete, including upgrading motor control parts, enhancing safety features, and adding more digital components & connectivity functions. Such full modernization projects only make sense when elevators age past 15-20 years. To OEMs, they are more than happy to offer such services, despite at a lower margin, to extend the lifespan of the maintenance contracts. Outside of major upgrades, small parts replacement could be anything from a new floor, new panel, brighter lights or getting a quieter fan. While maintenance crew / field engineers come into the building and conduct routine checks, they often suggest minor upgrades to be done almost immediately, where margins are as high as 30% or 40%. But the revenue contribution from these small items pales when compared to that of major modernization projects. Modernization sales are not as predictable and are driven more by backlog instead, much like new equipment. These projects are more discretionary and cyclical. Take retail landlords with tenets not paying rents during covid, they suffered cash flow issues and opted to delay elevators modernization projects. So that explained why backlog for modernization had been built in 2020-2021, and are now starting to be cleared in 2022-2023, massively boosting Kone’s service sales.

About 70% of the servicing costs are in field cost, which are mostly labor-related. The servicing business faces the same kind of labor challenges as we see in installation, where in the “impossible triangle” of margins, labor quality and labor recruitment/retention, companies usually only choose 2 out of 3. Service margins factors come from 3 areas. First is contract renewal and the built-in price escalation clause in the maintenance contracts. The good news is such clauses are usually auto renewed into the next period, but the bad news is the extent of the price increment more often matches with higher labor cost rather than surpassing it.

The second aspect is service labor productivity, which is a function of field engineers’ skills and route optimization. With predictive maintenance and more connected units, field engineers can anticipate problems based on past data trends and prepare spare parts beforehand. OEMs have better algorithms and smart scheduling to eliminate overlapped routes, allowing for more time spent on servicing rather than travelling. Another way to think about is to reduce service area coverage per field engineer, with smaller means higher route density (meaning more buildings served per road length traveled). The improvement in productivity is marked by an improvement in units served per labor. OTIS has 40% more maintenance units than Kone but has the same number of service employees, explaining the servicing margin gap of 7% (Each Kone field technician only serves 42 units). The downside of this model is that the cost advantage is localized. OTIS getting a denser servicing region in New York does not add to the cost advantage of servicing in Beijing.

Another way to understand this is to look at another servicing business. Take the case of Cintas, which offers uniform rental and cleaning services. The whole business is built upon the idea of optimizing route density. Cintas is trying to run less trips to reach more hotels/hospitals. Cintas’ superior IT infrastructure (e.g., investing in SAP) has optimized its servicing routes & scheduling and created unit cost gaps from Aramark and UniFirst. But compared to the elevator business, Cintas’ cost advantage is held back by its lack of pricing power and ease of switching.

Route optimization visualized, from OTIS investor day presentation 2022.

The last margin factor comes down to using digital sales and connected units to price servicing contracts higher. With each modernized elevator sold or upgraded, OEMs upsell software and digital service as a subsequent service package that come with higher margins. The elevator management software is usually well integrated with the building APIs to program the elevators to shut down without usage and minimize movement, allowing for smart energy management. Elevator equipment status and operating metrics are connected from the control room to mobile apps. The data is often sent to the servicing partner’s end to do remote monitoring, and predictive maintenance using AI.

If the servicing business is the true gem of an install-base business, why can’t customers outsource it to some third-party independent service provider (ISP)? The answer to whether OEM or ISP is better at aftermarket is circumstantial, depending on how niche and commoditized the subsequent attachment sales are and the entry barriers. When the product itself is complex with strict regulations, it requires massive initial investments to build product expertise as well as customer-specific knowledge. In this case, letting an OEM servicing the aftermarket seems an obvious choice, as seen in cases like industrial automation (Rockwell, Keyence), defense (Lockheed, BAE) and life science tools (Thermo Fisher, Danaher). But stripping out product complexity, third-party sellers win by offering a wide range of SKUs across different brands, managing niche offerings, and building robust distribution channels + local customer touchpoints. Cases in mind for this are auto parts (AutoZone, O’Reilly) and aircraft parts (Heico, Transdigm).

For elevators servicing, I inverted the problem by thinking about how OEMs do not win instead. First, conversion rate is not always 100% because: 1) installation frustrations (e.g., delay opening of new building), 2) improper installation and/or reliability issues, 3) existing relationship with another vendor from a different building, 4) lax regulation requirement and 5) price. OTIS’s 50% conversion rate and Kone’s 60% in China are mostly due to the last two reasons. In China, local regulation in many smaller cities is not as strict as major cities. So, the frequency of routine servicing is lower (once every 2-3 years), and the higher-margin predictive or remote servicing can be substituted by simply putting sensors inside the elevators.

The other aspect is cancellation rate / churn. A 10% churn is horrible, and a 1-3% churn on service is fantastic. Most regions have a 5-6% churn. OEMs lose contracts when they do not meet the required customer service level (e.g. on-time rate), when the service crew does not respond promptly to emergency calls. Competitors must propose a lower price along with superior service because customers don’t switch purely based on price alone. For a building manager, it is a pain in the ass to have a week-long delay for routine maintenance, and for ineffective field engineers that come back more than one time to fix the same problem. So, if a competitor can come on time + fix it on the spot + cheaper, that is the angle of attack that hits the switching factors, as it comes down to the reliability of the service. The maintenance market for low and mid-rise buildings is more competitive, ISPs go after them because such customers are more budget conscious and more poorly serviced by OEMs.

Customers often stick to existing OEMs due to relationship built over generations into better branding/reputation, or simply because they know these OEMs have the financial resilience to withstand economic shocks and liability claims (e.g., killing of passengers due to failed elevators under coverage) for next few decades. Like Auto Parts Aftermarket, parts availability plays an important role for high-rise, highly customizable designs, may have proprietary components that are only accessible in a cost-effective manner with the OEM. They would talk shit on ISPs, calling them out for cutting corners on conforming safety standard (poorly trained/less certified workers) on the cheap maintenance contracts to earn profits back on more parts replacement sales. OEMs put their own people into safety committee/counsel to influence new regulations/safety standards in their favor, and hence are better informed and prepared for implementing the changes needed.

ISPs refute such claims. They strike back by meeting service levels, offering low prices, localized touchpoints, faster respond time, and advocate for brand-agnostic maintenance. A guy closer to a problem would know how to fix the problem better. Smaller ISPs, being lean on management and cost structures, communicate directly between people on the ground and end customers. Public sectors, being more conscious of pricing and quality, do not buy into the OEM model, and government buildings are more often serviced by local ISPs, with contracts renewed on a yearly basis instead. Consultants, in a similar manner, often vouch for ISPs over OEMs because it’s their job to cut costs and meet service level. Many ISPs were former OEM directors frustrated by the sloppiness and inconsistent quality. They left the firm along with the customer connection to set up their own firms, drastically marked down the prices (e.g., 40%) by using non-union labor, while providing fast respond time, fast diagnosis, and part replacement promptly.

ISP usually goes after low-rise, smaller buildings because they simply do not have the national presence to service the larger accounts. So even if they win customer shares, they are not winning the highest quality profit share from them. If Marriott wants to find a servicing partner for their hotel elevators, they are naturally going to stick to the top 4 brands (OTIS, TK, Kone and Schindler) for the nationwide coverage in the US. Marriott is not going to hire 10 different local ISPs in 10 cities and negotiate one by one with them. Not only is quality consistency an issue, compromising absolute safety assurance is simply not worth saving that extra 2-3% of the operating costs, no matter how tight the profit margins are.

Market Structure of Japan Aftermarket Elevator Services, from JES website.

Japan Elevator Services (JES) is the pure-play listed ISP firm where the entire business model is built upon taking servicing shares away from OEM with lower price. In Japan, ISPs account for ~20% of the 1.1m elevator aftermarket while JES has ~40% market share among them (other 60% is shared by ~300 companies). The firm is fighting against the likes of Mitsubishi, Hitachi, Toshiba and Fujitec, Japanese OEMs that have given up on western markets to focus on Asia only. But upon further digging, JES services its ~95K maintenance base at ASP of ~$3.2K, roughly at half the price of, say Hitachi’s ASP at ~$6.5K for its ~380K units under maintenance. If we also account for Hitachi regional sales mix of 55/45 in China/Japan, since China has much lower ASP, the Japanese servicing price is higher than this blended $6.5K figure. Despite lower prices, JES does not compromise on quality. Parts availability is not an issue because of strong local supply chains, and JES stores OEM parts in eight part-centers nationwide, where workers work 24/7 shifts to stock up and send out the right parts when there is an emergency call. The model works as JES grew sales at 15-18% for the last 10 years by expanding both ISP penetration and market share. JES’ maintenance base expanded 3x from a low base of ~32K since 2015, labor efficiency improved when route density increases within same cities, translating into 5% GP margins expansion and EBIT margins went up from 6% to 15% for past 8 years.

But why is Japan so unique? First is the environment. Japan buildings/population are densely packed, urbanization rate is 90%, and JES focuses on these large urban cities6 where route optimization is further enhanced with cross-brand maintenance to create a cost advantage. Second is labor. Japanese people are obsessed with efficiency and have strong work ethics. The nation is digitally-savvy, and JES equips the right digital tools for field engineers and sets up robust monitoring systems (WES) in its control centers. Once labor bottleneck is overcome, the playing field is equalized. On the other hand, Japanese OEMs don’t always have the right focus since they are conglomerate firms (only 10% of sales in Hitachi comes from elevators). They put more effort in adding new features on the new equipment sales (buildings are renovated more often in Japan) and treat servicing more of an afterthought, they are less willing to service competitors’ brands, and have shifted a lot of their effort towards fighting new equipment shares in China. It has the same 38% GP margin that matches OTIS on its servicing segment GP margin of 38%, as well as why it has a decent return of capital at ~20%. The stock is expensive, and the moat doesn’t seem to be unique to JES alone as far as I see, so sustainability of growth/returns is in question. JES also knows that new unit growth peaked after 2007, and overall maintenance base in Japan is only growing at 20K per year (<2%), and management is planning to steal another 5% share from OEMs by 2027 and eying for an EBIT margin target of 20%. But JES cannot grow double digits forever by stealing domestic OEM shares alone, so it has expanded into India and Southeast Asia markets (cleverly avoided China), where I am not so sure if they can win in those regions as well with narrower pricing gaps between OEMs and ISPs.

JES’s plan to overtake a larger share of OEM servicing market, from JES earnings presentation 2023.

Schindler is a Swiss company founded, and still owned and controlled by the Schindler family (~70% voting rights) today. It has accumulated over a global maintenance base of 1.7m ranking #2 behind OTIS. Schindler sales revenue is larger than Kone and behind OTIS, but unit sales rank #3 globally with 150K units sold each year. Schindler’s escalator and moving walkway products are industry-leading flagship products despite only accounting for about 10% in sales. Among the E&E industry, escalator only accounts for 5% of the TAM, not because of unit price, but smaller volumes. Escalator sales are driven by strong capex cycles because demands are concentrated towards retail and transportation. After the disposal of ALSO, Schindler became a more streamlined pure-play elevator & escalator company, and its OP margins didn’t fluctuate much, moving between 10-11% in most years. Schindler has been moderately profitable and grew its organic sales at MSD, better than OTIS but below Kone.

Although Schindler was the first major elevator foreign brand to enter China in 1980, it currently has a weaker market share of ~7%, compared to Kone’s 18% and OTIS’ 10%. Its elevator product in China doesn’t stand out much unlike Kone, and the company is not agile enough to respond fast to local changes and suffered same distribution channel issues as OTIS. Schindler’s sales mix between equipment and service is about 45/55 split, China accounts for only 10-13% of revenue, and ASP metrics are more or less the same as OTIS and Kone. Equipment margin is lowest among the 3, service margin (17%) is estimated to be higher than Kone (15%, also a guess) but lower than OTIS (23%, reported). Operating metrics-wise, Schindler is neither too impressive nor too lousy, which makes me wonder why its stock is valued at a premium. The share structure of Schindler is a bit more nuanced. There are registered share vs participations, where participation shares cannot vote, and each holder or registered share cannot exercise more than 3% voting rights. And the family is holding onto the registered shares (but are exempted from the 3% rule) to keep a fight fist over how the company should be run. I feel like corporate governance is a concern in this firm, I fear that minority shareholders will get squeezed by majority shareholders.

The elevators & escalators industry is ~$80B in size that grows at a modest MSD (DM is LSD, EM is HSD). In thinking about future new sales units’ growth, we can attribute the growth to drivers in population / new floor space multiple by elevator intensity (elevators per population or per sqm). There is no doubt about industry relevancy and long-term demand. There are ~20 million elevators in the world. This number is peanut compared to the ~5 billion buildings because most buildings are on a single floor without the need for an elevator (85% of the US buildings are low-rise). But living in one of the most densely populated cities like Singapore means taller buildings are needed to maximize the vertical utilization of each area of land, preserving the scarce land resources for the island nation. Well, considered that the world is expected to be 70% urbanized compared to 55% now, we should see more cities becoming more like Singapore, building up tall residential housing and commercial skyscrapers to accommodate millions of population inflow, especially in Asia and Africa where population density is high.

Operating metrics compared, data from official sources.

The industry does get consolidated over time, but similar to Atlas Copco, it was through small-size local acquisitions on aftermarket businesses rather than major acquisitions. In 2007, the European Union fined Schindler, along with other major elevator brands, for a price-fixing cartel. The amount of fine is small, but the message is strong. Anti-trust regulators know that this is a major oligopoly and are not going to approve mergers among major brands. Schindler triggered a legal war on the proposed merger between TK Elevator and Kone and had successfully blocked the deal. My point is elevator remains a sort of Mexican standoff situation where each local region is dominated by small number of strong brands. That’s why I think this industry really comes down to the competitive landscape and the threat of ISP over OEMs. For this, my conclusion is that I would bet on OEMs in DMs + China and ISPs on EMs + Japan.

OTIS sales breakdown and drivers, from my own valuation model.

Equipment sales in the short term are driven by order book volume (which is cyclical) and technicians’ availability to clear them. End of this year order book = last year order book + new orders intake - old order cleared. Book to bill ratio (new order coming in divided by old orders converting to sales as work is done) is a useful metric to indicate whether the order book is growing or falling. If this sounds confusing, a rule of thumb is to imagine a bathtub with water flowing in from a faucet (new order intake), water flowing through the drain (revenue recognized), and current water level as order book. Servicing business is even more clear cut. Maintenance revenue is maintenance base multiples by service ASP, and margins are driven by contract pricing and route density measured by units per service labor. On top of new equipment unit growth, how fast does the maintenance base grow is a matter of conversion rate and retention rate, subjected to ISP competition. Modernization sales are similar to new equipment using order book, but for simplicity we can just lump it along with maintenance as blended service ASP. Yeah, modeling out order/backlog is not difficult on excel spreadsheets, I think what’s more important over the long-term is not guessing order book trend within a cycle, but finding out if the company is likely going to win across the cycles and estimating long-term organic sales growth potential.

Let’s summarize the thesis on each company. OTIS has better brand and quality perception and the largest maintenance base with best-in-class service economics. Kone is innovative, the products are more suited to local demands in each region, but its install base is blended with 1/3 of less profitable China units. If possible, I would probably pay a visit or pull some strings to talk to some Chinese real estate developers or property managers to find out more about the conversion and retention factors there. China could be a thesis breaker for Kone. Schindler is a decent brand, margins are stable, growth has been okay, but I am less fond of its corporate governance. Japan Elevator is quite interesting. The investment case for ISP market as a whole is quite clear, but I might need more time to figure out OEM parts sourcing strategies and competitive landscape among ISPs to further strengthen the thesis, I would not place much value on the model working elsewhere, but domestic share expansion should be enough for the company to continue to grow for next 3-5 years, but I am less sure on 10-15 years outlook without having the equipment sales to bring in new units.

Nonetheless, I feel that all 4 companies are within my circle of competence to value. Elevator revenue is visible, margins are well-protected, business is asset-light, its quality is high, so I would put a fair value around 25x. OTIS is traded at 25x P/E with an FCF yield of 5%. My calculation churns out a low LT organic growth expectation of 2-3%. Let’s say margin swing back to 18%, and dividend yield of 1%, in total it would reward me roughly 7% IRR, about the same as 5+2% calculated from FCF yield’s perspective. If I flex the conversion rate high into 70%+, reduce the churn assumption down to 2% and boost the maintenance base to 2.8 million units as targeted by management, IRR will improve to 9%. Kone’s unit growth is slowing with China weakening, and with 65% conversion rate and a 6% churn assumed, maintenance base is about the same. But the competitive landscape is becoming more rational, I expect unit and service ASP to expand allowing for margin expansion to 14%, still below the 16% target set by management. This gives me an IRR of ~10%. Schindler is similar to Kone but with lower growth, and multiple expansion is a risk factor not a return driver, so overall IRR remains only LSD. My understanding of Schindler is the weakest among the 4. As for Japan Elevator Services, again the stock is expensive, even with a 16% EPS growth coming from 5% market share expansion + increasing ASP + margin improvement into 20%, I am less confident to place a fair multiple at anywhere more than 30x, and that would give me a 5% IRR with a 5-year period. For OTIS, Schindler and JES, their valuations are too high and I shall wait for better opportunities. If all 4 companies are traded with the same multiple, I'll pick JES over the rest because the thesis is so much stronger. Kone has decent expected returns mainly due to higher dividend yields and my thesis hinges too much on pricing improvement in China, so I need a bit more margin of safety to feel comfortable to own its stocks.

OTIS 0.00%↑ $KNEBV SCHP 0.00%↑ and $6544

Notes:

1. Global sourcing strategy illustrated, from Mitsubishi Electric Elevator Presentation

2. Different types of elevators, from TK elevators here and here.

3. Growth of Chinese elevator demand driven by higher urbanization rate and elevator density

4. New unit sold from China has slowed down, from OTIS investor day presentation 2020.

5. Kone (and OTIS) are increasing focusing on larger developers to increase sales density per customer, from Kone’s Investor Presentation 2017.

6. JES focused on densely populated areas, left from JES earnings presentation 2018, right from Wikimedia.

good note, thanks. I have been recently looking at Japan Elevator Service. Seems like a very well run company and it has a strong track record. Where did you find the stat on ASP for JES and competitors?

Enjoyed the piece, great work. I disagree with this part on pricing power/switching costs. “Pricing power resulting from a high switching cost. Since elevator maintenance cost accounts for merely ~3% of the building’s operating budget, it is not worth the effort to look for another servicing partner and save a minuscule amount of budget.” The reason for 90%+ retention rates is inertia not lock in. These OEMs have service customers not hostages. True that it is ORMs right to lose. As long as they provide good service they will keep the work but If you speak to ISPs or PE in the space they will testify to price competition/ low switching costs. Curious your thoughts.